The Mirage III in SAAF Service (Part 1)

Origin of the Mirage III

The Mirage III family grew out of French government studies started in 1952 that led in early 1953 to a specification for a lightweight, all-weather interceptor capable of climbing to 18,000 m (59,040 ft) in six minutes and able to reach Mach 1.3 in level flight.

.jpg)

Dassault's response to the specification was the Mystère-Delta 550, (above) a diminutive and sleek jet that was to be powered by twin Armstrong Siddeley MD30R Viper after-burning turbojets, each with thrust of 9.61 kN (2,160 lbf). A SEPR liquid-fuel rocket motor was to provide additional burst thrust of 14.7 kN (3,300 lbf). The aircraft had a tailless delta configuration, with a 5% chord (ratio of airfoil thickness to length) and 60 degree sweep.

After some redesign, reduction of the fin to more rational size, installation of afterburners and rocket motor, and renaming to Mirage I, in late 1955, the prototype attained Mach 1.3 in level flight without rocket assist, and Mach 1.6 with the rocket.

Mirage I (note tail and exhaust configuration)

Dassault then considered a somewhat bigger version, the Mirage II, with a pair of Turbomeca Gabizo turbojets, but no aircraft of this configuration was ever built. The Mirage II was bypassed for a much more ambitious design that was 30% heavier than the Mirage I and was powered by the new SNECMA Atar after-burning turbojet with thrust of 43.2 kN (9,700 lbf). The Atar was an axial flow turbojet, derived from the German World War II BMW 003 design.However, the small size of the Mirage I restricted its armament to a single air-to-air missile, and even before this time it had been prudently decided the aircraft was simply too tiny to carry a useful armament load. After trials, the Mirage I prototype was eventually scrapped.

The new fighter design was named the Mirage III. It incorporated the new area ruling concept, where changes to the cross section of an aircraft were made as gradual as possible, resulting in the famous "wasp waist" configuration of many supersonic fighters. Like the Mirage I, the Mirage III had provision for a SEPR rocket engine.

Relative size and footprint

The success of the Mirage III prototype resulted in an order for 10 pre-production Mirage IIIAs. These were almost two meters longer than the Mirage III prototype, had a wing with 17.3% more area, a chord reduced to 4.5%, and an Atar 09B turbojet with after-burning thrust of 58.9 kN (13,230 lbf). The SEPR rocket engine was retained, and the aircraft were fitted with Thomson-CSF Cyrano Ibis air intercept radar, operational avionics, and a drag chute to shorten landing roll. The prototype Mirage III flew on 17 November 1956, and attained a speed of Mach 1.52 on its tenth flight. The prototype was then fitted with manually operated intake half-cone shock diffusers, known as souris ("mice"), which were moved forward as speed increased to reduce inlet turbulence. The Mirage III attained a speed of Mach 1.8 in September 1957.

The first Mirage IIIA flew in May 1958, and eventually was clocked at Mach 2.2, making it the first European aircraft to exceed Mach 2 in level flight. The tenth IIIA was rolled out in December 1959. One was fitted with a Rolls-Royce Avon 67 engine with thrust of 71.1 kN (16,000 lbf) as a test model for Australian evaluation, with the name "Mirage IIIO". This variant flew in February 1961, but the Avon powerplant was not adopted.

French Mirage IIICs

The first major production model of the Mirage series, the Mirage IIIC, first flew in October 1960. The IIIC was largely similar to the IIIA, though a little under a half meter longer and brought up to full operational fit. The IIIC was a single-seat interceptor, with an Atar 09B turbojet engine, featuring an "eyelet" style variable exhaust.

DEFA 30mm revolver auto-cannon as installed on the Mirage III and F1

The Mirage IIIC was armed with twin 30 mm DEFA revolver-type cannon, fitted in the belly with the gun ports under the air intake. Early Mirage IIIC production had three stores pylons, one under the fuselage and one under each wing, but another outboard pylon was quickly added to each wing, for a total of five. The outboard pylon was intended to carry an AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missile, later replaced by the Matra Magic.

Although provision for the rocket engine was retained, by this time the day of the high-altitude bomber seemed to be over, and the SEPR rocket engine was rarely or never fitted in practice. In the first place, it required removal of the aircraft's cannon, and in the second, apparently it had a reputation for setting the aircraft on fire !

The space for the rocket engine was used for additional fuel, and the rocket nozzle was replaced by a ventral fin at first, and an airfield arresting assembly later.

A total of 95 Mirage IIICs were obtained by the French Air Force (Armée de l'Air, AdA ), with initial operational deliveries in July 1961. The Mirage IIIC remained in service with the AdA until 1988.

The Armée de l'Air also ordered a two-seat Mirage IIIB operational trainer, which first flew in October 1959. The fuselage was stretched about a meter (3 ft 3.5 in) and both cannons were removed to accommodate the second seat. The IIIB had no radar, and provision for the SEPR rocket was deleted, although it could carry external stores.

The AdA ordered 63 Mirage IIIBs (including the prototype), including five Mirage IIIB-1trials aircraft, ten Mirage IIIB-2(RV) in-flight refueling trainers with dummy nose probes, used for training Mirage IVA bomber pilots, and 20 Mirage IIIBEs, with the engine and some other features of the multi role Mirage IIIE. One Mirage IIIB was fitted with a fly-by-wire flight control system in the mid-1970s and re-designated Mirage IIIB-SV (Stabilité Variable); this aircraft was used as a test bed for the system in the later Mirage 2000.

While the Mirage IIIC was being put into production, Dassault was also considering a multi role/strike variant of the aircraft, which eventually materialized as the Mirage IIIE. The first of three prototypes flew on 1 April 1961.

The Mirage IIIE differed from the IIIC interceptor most obviously in having a 30 cm (11.8 in) forward fuselage extension to increase the size of the avionics bay behind the cockpit. The stretch also helped increase fuel capacity, as the Mirage IIIC had marginal range and improvements were needed. The stretch was small and hard to notice, but the clue is that the bottom edge of the canopy on a Mirage IIIE ends directly above the top lip of the air intake, while on the IIIC it ends visibly back of the lip.

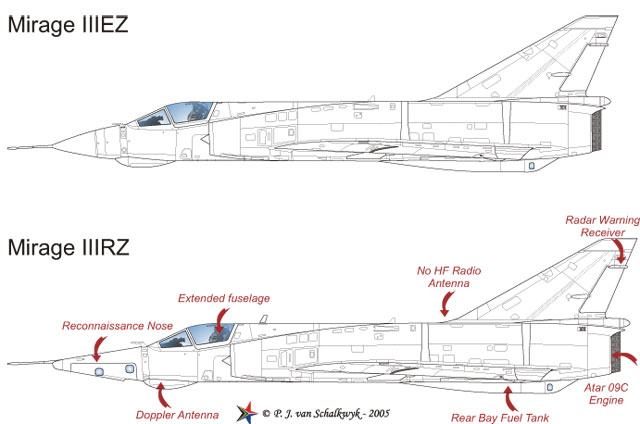

Many Mirage IIIE variants were also fitted with a Marconi continuous-wave Doppler navigation radar radome on the bottom of the fuselage, under the cockpit. However, while no IIICs had this feature, it was not universal on all variants of the IIIE. A similar inconsistent variation in Mirage fighter versions was the presence or absence of an HF antenna that was fitted as a forward extension to the vertical tailplane. On some Mirages, the leading edge of the tailplane was a straight line, while on those with the HF antenna the leading edge had a sloping extension forward. The extension appears to have been generally standard on production Mirage IIIAs and Mirage IIICs, but only appeared in some of the export versions of the Mirage IIIE.

The IIIE featured Thomson-CSF Cyrano II dual mode air / ground radar; a radar warning receiver (RWR) system with the antennas mounted in the vertical tailplane; and an Atar 09C engine, with a petal-style variable exhaust.

The first production Mirage IIIE was delivered to the AdA in January 1964, and a total of 192 were eventually delivered to that service.

Total production of the Mirage IIIE, including exports, was substantially larger than that of the Mirage IIIC, including exports, totaling 523 aircraft. In the mid-1960s one Mirage IIIE was fitted with the improved SNECMA Atar 09K-6 turbojet for trials, and given the confusing designation of Mirage IIIC2.

Exports and license production

The French AdA obtained 50 production Mirage IIIRs, not including two prototypes. The Mirage IIIR preceded the Mirage IIIE in operational introduction. The AdA also obtained 20 improved Mirage IIIRD reconnaissance variants, essentially a Mirage IIIR with an extra panoramic camera in the most forward nose position, and the Doppler radar and other avionics from the Mirage IIIE.

Exports

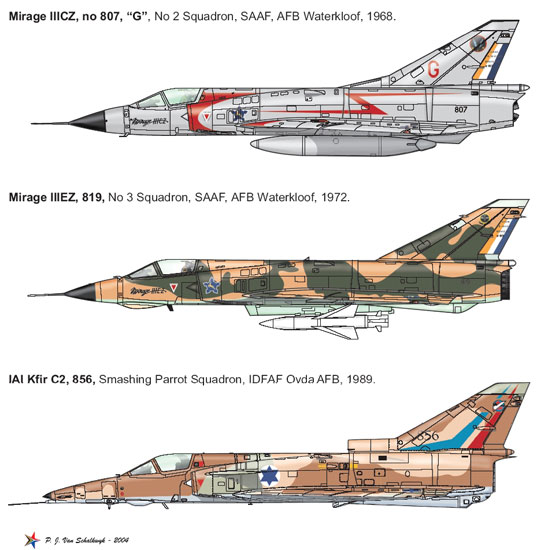

The largest export customers for Mirage IIICs built in France were Israel as the Mirage IIICJ and South Africa as the Mirage IIICZ.

Some export customers obtained the Mirage IIIB, with designations only changed to provide a country code. Such as the Mirage IIIDA for Argentina, Mirage IIIDBR and Mirage IIIDBR-2 for Brazil. Mirage IIIBJ for Israel, Mirage IIIDL for Lebanon, Mirage IIIDP for Pakistan, Mirage IIIBZ and Mirage IIIDZ and Mirage IIID2Z for South Africa, Mirage IIIDE for Spain and Mirage IIIDV for Venezuela.

Some export customers obtained the Mirage IIIB, with designations only changed to provide a country code. Such as the Mirage IIIDA for Argentina, Mirage IIIDBR and Mirage IIIDBR-2 for Brazil. Mirage IIIBJ for Israel, Mirage IIIDL for Lebanon, Mirage IIIDP for Pakistan, Mirage IIIBZ and Mirage IIIDZ and Mirage IIID2Z for South Africa, Mirage IIIDE for Spain and Mirage IIIDV for Venezuela.

After the outstanding Israeli success with the Mirage IIIC, scoring kills against Syrian Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-17s and MiG-21 aircraft and then achieving a formidable victory against Egypt, Jordan, and Syria in the Six-Day War of June 1967, the Mirage III's reputation was greatly enhanced. The "combat-proven" image and relatively low cost made it a popular export success.

The aircraft remained a formidable weapon in the hands of Pakistan Air force in No. 5 Squadron (Pakistan Air Force), which was fully operational by the 1971 War. Flying out from Sargodha, along with a detachment in Mianwali, these were extensively used for ground attacks. No Mirage was lost in the war. PAF defined their own work package for major Depot level & Overhaul making them world's experts on the Mirage classic. The Mirage fleet is currently being modified to accommodate Aerial Refueling and to carry Hatf-VIII (Ra'ad) cruise missiles. In wake of delays from JF-17 Thunder, Mirages continue to play a major part in the defense of Pakistan airspace through Pakistani's Engineers ingenuity and engineering skills.

A good number of IIIEs were built for export as well, being purchased in small quantities by Argentina as the Mirage IIIEA and Mirage IIIEBR-2 Brazil as the Mirage IIIEBR, Lebanon as the Mirage IIIEL,Pakistan as the Mirage IIIEP, South Africa as the Mirage IIIEZ, Spain as the Mirage IIIEE, and Venezuela as the Mirage IIIEV, with a list of subvariant designations, with minor variations in equipment fit.

Dassault believed the customer was always right, and was happy to accommodate changes in equipment fit as customer needs and budget required. Pakistani Mirage 5PA3, for example, were fitted with Thomson-CSF Agave radar with capability of guiding the Exocet anti-ship missile.

Some customers obtained the two-seat Mirage IIIBE under the general designation Mirage IIID, though the trainers were generally similar to the Mirage IIIBE except for minor changes in equipment fit. In some cases they were identical, since two surplus AdA Mirage IIIBEs were sold to Brazil under the designation Mirage IIIBBR, and three were similarly sold to Egypt under the designation Mirage 5SDD. New-build exports of this type included aircraft sold to Abu Dhabi, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Egypt, Gabon, Libya, Pakistan, Peru, Spain, Venezuela, and Zaire.

Difference between EZ and RZ variants

Export versions of the Mirage IIIR were built for Pakistan as the Mirage IIIRP and South Africa as the Mirage IIIRZ, and Mirage IIIR2Z with an Atar 9K-50 jet engine.

Export versions of the IIIR recce aircraft were purchased by Abu Dhabi, Belgium, Colombia, Egypt, Libya, Pakistan, and South Africa. Some export Mirage IIIRDs were fitted with British Vinten cameras, not OMERA cameras. Most of the Belgian aircraft were built locally.

Israel

The IDF/AF purchased three variants of the Mirage III

70 Mirage IIICJ single-seat fighters, received between April 1962 and July 1964.

Two Mirage IIIRJ single-seat photo-reconnaissance aircraft, received in March 1964.

Four Mirage IIIBJ two-seat combat trainers, three received in 1966 and one in 1968.

The Israeli AF Mirage III fleet went through several modifications during their service life.

Over the demilitarized zone on the Israeli side of the border with Syria, a total of six MiGs were shot down the first day Mirages fought the MiGs. In the Six-Day War, except for 12 Mirages (four in the air and eight on the ground), left behind to guard Israel from Arab bombers, all the Mirages were fitted with bombs, and sent to attack the Arab air bases. However the Mirage's performance as a bomber was limited. During the following days Mirages performed as fighters, and out of a total of 58 Arab aircraft shot down in air combat during the war, 48 were accounted for by Mirages.

License production: In the 1973 Yom Kippur War, the Mirage performed in air-to-air operations only. At least 26 Mirages and Neshers were lost in air-to-air combat during the war.

The Mirage IIIE was also built under license in Australia, Belgium and Switzerland.

Variants

M.D.550 Mystere-Delta

Single-seat delta-wing interceptor-fighter prototype, fitted with a delta vertical tail surface, equipped with a retractable tricycle landing gear, powered by two 7.35 kN (1,653 lbf) thrust M.D.30 (Armstrong Siddeley Viper) turbojet engines; one built.

Mirage I

Revised first prototype, fitted with a swept vertical tail surface, powered by two reheated M.D.30R turbojet engines (9.61 kN (2,160 lbf with reheat), also fitted with a 15 kN (3,370 lbf) thrust SEPR 66 auxiliary rocket motor.[2]

Mirage II

Single-seat delta-wing interceptor-fighter prototype, larger version of the Mirage I, powered by two Turbomeca Gabizo turbojet engines; one abandoned incomplete

Mirage III-001

Prototype, initially powered by a 44.12 kN (9,920 lbf) thrust Atar 101G1 turbojet engine, later refitted with 43.15 kN (9,700 lbf) Atar 101G-2 and also fitted with a SEPR 66 auxiliary rocket motor; one built.[2]

Mirage IIIA

Pre-production aircraft, with a lengthened, area ruled fuselage and powered by a 42.08 kN (9,460 lbf) dry and 58.84 kN (13,228 lbf) with reheat Atar 9B turbojet engine, also with provision for 13.34 kN (3,000 lbf) SEPR 84 auxiliary rocket motor. Fitted with Dassault Super Aida or Thomson-CSF Cyrano Ibis radar. Ten built for the French Air Force.

Mirage IIIB

Two-seat tandem trainer aircraft fitted with one piece canopy. Lacks radar, cannon armament and provision for booster rocket. Prototype (based on the IIIA) first flown on 20 October 1959. Followed by 26 production IIIBs based on IIIC for French Air Force and one for Centre d'essais en vol (CEV) test centre.[9][10]

Mirage IIIB-1 : Trials aircraft. Five built.[10]

Mirage IIIB-2(RV) : Inflight refuelling training aircraft for Mirage IV force, fitted with dummy refuelling probe in nose. Ten built.[11]

Mirage IIIBE : Two-seat training aircraft based on Mirage IIIE for the French Air Force, similar to the Mirage IIID. 20 built.

Mirage IIIBJ : Mirage IIIB for Israeli Air Force. Five built.

Mirage IIIBL : Mirage IIIBE for Lebanon Air Force.

Mirage IIIBS : Mirage IIIB for the Swiss Air Force; four built.

Mirage IIIBZ : Mirage IIIB for the South African Air Force; three built.

Mirage IIIC

Single-seat all-weather interceptor-fighter aircraft, with longer fuselage (14.73 m (13 ft 11¾ in)) than the IIIA and equipped with a Cyrano Ibis radar. The Mirage IIIC was armed with two 30 mm cannons, with a single Matra R.511, Nord AA.20 orMatra R530 air-to-air missile under the fuselage and two AIM-9 Sidewinder missiles under the wings. It was powered by an Atar 9B-3 turbojet engine, which could be supplemented by fitting an auxiliary rocket motor in the rear fuselage if the cannon were removed. 95 were built for the French Air Force.

Mirage IIICJ : Mirage IIIC for the Israeli Air Force, fitted with simpler electronics and with provision for the booster rocket removed. 72 delivered between 1961 and 1964.

Mirage IIICS : Mirage IIIC supplied to Swiss Air Force in 1962 for evaluation and test purposes. One built.

Mirage IIICZ : Mirage IIIC for the South African Air Force. 16 supplied between December 1962 and March 1964.

Mirage IIIC-2 : Conversion of French Mirage IIIE with Atar 09K-6 engine. One aircraft converted, later re-converted to Mirage IIIE.

Mirage IIID

Two-seat trainer version of the Mirage IIIE, powered by 41.97 kN (9,369 lbf) dry and 58.84 kN (13,228 lbf) with reheat Atar 09-C engine. Fitted with distinctive strakes under the nose. Almost identical aircraft designated Mirage IIIBE, IIID and 5Dx depending on customer.

Mirage IIID : Two-seat training aircraft for the RAAF. Built under licence in Australia; 16 built.

Mirage IIIDA : Two-seat trainer for the Argentine Air Force. Two supplied 1973 and a further two in 1982.

Mirage IIIDBR : Two-seat trainer for the Brazilian Air Force, designated F-103D. Four newly-built aircraft delivered from 1972. Two ex-French Air Force Mirage IIIBEs delivered 1984 to make up for losses in accidents.

Mirage IIIDBR-2 : Refurbished and updated aircraft for the Brazilian Air Force, with more modern avionics and canard foreplanes. Two ex-French aircraft sold to Brazil in 1988, with remaining two DBRs upgraded to same standard.

Mirage IIIDE : Two-seat trainer for Spanish Air Force. Six built with local designation CE.11.

Mirage IIIDP : Two-seat trainer for the Pakistan Air Force. Five built.

Mirage IIIDS : Two-seat trainer for the Swiss Air Force. Two delivered 1983.

Mirage IIIDV : Two-seat trainer for the Venezuelan Air Force; three built.

Mirage IIIDZ : Two-seat trainer for the South African Air Force; three delivered 1969.

Mirage IIID2Z : Two-seat trainer for the South African Air Force, fitted with an Atar 9K-50 turbojet engine; giving 49.2 kN (11,055 lbf) thrust dry and 70.6 kN (15,870 lbf) with reheat. Eleven built.

Mirage IIIE

Single-seat tactical strike and fighter-bomber aircraft, with 30 cm (11¾ in) fuselage plug to accommodate an additional avionics bay behind the cockpit. Fitted with Cyrano II radar with additional air-to-ground modes compared to Mirage IIIC, improved navigation equipment, including TACAN and a Doppler radar in undernose bulge. Powered by an Atar 09C-3 turbojet engine. 183 built for the French Air Force

Mirage IIIEA : Mirage IIIE for the Argentine Air Force. 17 built.

Mirage IIIEBR : Mirage IIIE for the Brazilian Air Force; 16 built, locally designated F-103E.

Mirage IIIEBR-2 : Refurbished and updated aircraft for the Brazilian Air Force, with canard foreplanes. Four ex-French aircraft sold to Brazil in 1988, with surviving Mirage IIIEBRs upgraded to same standard.

Mirage IIIEE : Mirage IIIE for the Spanish Air Force, locally designated C.11. 24 delivered from 1970.

Mirage IIIEL : Mirage IIIE for the Lebanese Air Force, omitting doppler radar, including HF antenna. 10 delivered from 1967 and 1969.

Mirage IIIEP : Mirage IIIE for the Pakistan Air Force. 18 delivered 1967–1969.

Mirage IIIEV : Mirage IIIE for the Venezuelan Air Force, omitting doppler radar. Seven built. Survivors upgraded to Mirage 50EV standard.

Mirage IIIEZ : Mirage IIIE for the South African Air Force; 17 delivered 1965–1972.

Mirage IIIO

Single-seat all-weather fighter-bomber aircraft for the Royal Australian Air Force. Single prototype powered by 53.68 kN (12,000 lbf) dry thrust and 71.17 kN (16,000 lbf) Rolls-Royce Avon Mk 67 turbojet engine, but order placed for aircraft based on Mirage IIIE, powered by Atar engine in March 1961. 100 aircraft built, of which 98 were built under licence in Australia. The first 49 were Mirage IIIO(F) interceptors which were followed by 51 Mirage IIIO(A) fighter bombers, with survivors brought up to a common standard later.

Mirage IIIR

Single-seat all-weather reconnaissance aircraft, with radar replaced by camera nose carrying up to five cameras. Aircraft based on IIIE airframe but with simpler avionics similar to that fitted to the IIIC and retaining cannon armament of fighters. Two prototypes and 50 production aircraft built for the French Air Force.[33][34]

Mirage IIIRD : Single-seat all-weather reconnaissance aircraft for the French Air Force, equipped with improved avionics, including undernose doppler radar as in the Mirage IIIE. Provision to carry infra-red linescan Doppler navigation radar or Side looking airborne radar (SLAR) in interchangeable pod. 20 built

Mirage IIIRJ : Single-seat all-weather reconniassance aircraft of the Israeli Air Force. Two Mirage IIICZs converted into reconnaissance aircraft.

Mirage IIIRP : Export version of the Mirage IIIR for the Pakistan Air Force; 13 built.

Mirage IIIRS : Export version of the Mirage IIIR for the Swiss Air Force; 18 built.

Mirage IIIRZ : Export version of the Mirage IIIR for the South African Air Force; four built.

Mirage IIIR2Z : Export version of the Mirage IIIR for the South African Air Force, fitted with an Atar 9K-50 turbojet engine; four built.

Mirage IIIS

Single-seat all-weather interceptor fighter aircraft for the Swiss Air Force, fitted with a Hughes TARAN 18 radar and fire-control system, armed with AIM-4 Falcon and Sidewinder air-to-air missiles. Built under licence in Switzerland; 36 built.

Mirage IIIT

One aircraft converted into an engine testbed, it was fitted with a 9000-kg (19,482-lb) SNECMA TF-106 turbofan engine.

Mirage IIIX

Proposed version, announced in 1982, fitted with updated avionics and fly-by-wire controls, powered by an Atar 9K-50 turbojet engine. Original designation of the Mirage 3NG.

72dpi.jpg)