Dakota Part 5:

Douglas AC-47 Spooky / Puff, the Magic Dragon / Dragon Dak

The Douglas AC-47 Spooky (also nicknamed "Puff, the Magic Dragon") was the first in a series of gunships developed by the United States Air Force during the Vietnam War. More firepower than could be provided by light and medium ground-attack aircraft was thought to be needed in some situations when ground forces called for close air support.

British "Waist-gunners" using Lewis Guns in WW2,

mostly for anti-aircraft purposes rather than ground attack

Late in World War II, an Army Air Force lieutenant named Gilmour C. MacDonald had come up with the idea of mounting side-firing weapons in aircraft for the ground attack mission. The pilot of a conventional attack aircraft had to make a pass on a target and fire his weapons, then come around for another pass. The pilot of an attack aircraft with side-firing weapons could simply perform a banking "pylon turn" around a target, line up the target along his wingtip, and then hose it down with a "cone of fire" for as long as ammunition held out.

Nothing came of the idea until 1961, when MacDonald, by then a USAF lieutenant colonel, brought it up again and managed to inspire a set of shoestring demonstrations of the concept. By 1964, it was the right idea in the right place. The USAF was trying to come to grips with the difficulties of fighting the growing jungle war in Southeast Asia, in particular casting about for a way to perform effective close air support for ground operations.

In August of that year, the war had undergone a drastic escalation with the the Tonkin Gulf incident. In November, a USAF captain named Ronald W. Terry sold the idea of a gunship to the brass, and was authorized to put together two gunships quickly for a combat evaluation. MacDonald was the father of the idea of the side-firing gunship, but Terry was the one who would make it work.

The initial two Dakota gunships were in Vietnam by December and in combat before the end of the year. The gunships were originally given the designation of "FC-47D", but this was quickly changed to "AC-47D" in response to loud complaints by fighter pilots that calling any kind of a C-47 a "fighter" was really stretching the definition of the term.

The AC-47Ds was fitted with three 7.62 millimeter (0.30 caliber) Gatling-style Miniguns firing out the left side of the aircraft. The Miniguns had a selectable rate of fire of 3,000 or 6,000 rounds per minute, and the gunship typically carried about 24,000 rounds of ammunition. Early gunships used improvised cargo-hold mounts for standard SUU-11A/A Minigun pods, the pod having been designed as an underwing store. Later gunships carried GAU-2B/A Miniguns more specifically rigged for the task, and then the far more satisfactory MXU-470/A Miniguns, which used an ammunition drum instead of a belt-feed from ammunition cans, with great improvement in convenience and reliability. After some experience, the guns would be fixed pointing 12 degrees downward, reducing the aircraft bank angle required for attacks.

Electrically operated miniguns

Ballistic armor curtains were fitted to the left side of the aircraft to protect crew and systems; new radio and navigation equipment were installed; a Mark 20 gun sight salvaged from the Douglas A-1 Skyraider attack aircraft was fitted to the cockpit left-side window; and a trigger button from the same source was attached to the pilot's control wheel. The AC-47Ds also carried a bin of illumination flares for night fighting next to the cargo door, with the flares tossed out of the aircraft by the flight crew by hand. The bin was later armored to prevent the flares from being set off by ground fire.

Vietnamese who observed attacks by the gunships compared them to roaring, fire-spouting dragons, and so the gunships acquired the name "Puff", after a contemporary pop tune, "Puff the Magic Dragon". They were more informally called "Spooky" after their radio call-sign, and were well-liked by US ground forces for their ability to literally rip enemy assaults to shreds.

The modified craft's primary function was close air support for ground troops. Other armament configurations could also be found on similar C-47-based aircraft around the world. The guns were actuated by a control on the pilot's yoke whereby he could control the guns either individually or together, although gunners were also among the crew to assist with gun failures and similar issues. It could orbit the target for hours, providing suppressing fire over an elliptical area approximately 52 yd (47.5 m) in diameter, placing a round every 2.4 yd (2.2 m) during a three-second burst. The aircraft also carried flares it could drop to illuminate the battleground.

Spent casings after a Vietnam mission

The AC-47 had no previous design to gauge how successful it would be because it was the first of its kind. The USAF found itself in a precarious situation when requests for additional gunships began to come in because it simply lacked miniguns to fit additional aircraft after the first two conversions. The next four aircraft were equipped with 10 .30 caliber AN/M2 machine guns. However, these weapons, using World War II and Korean War ammunition stocks, were quickly discovered to jam easily, produce large amounts of gases from firing, and, even in 10-gun groups, only provide the density of fire of a single minigun. All four of these aircraft were retrofitted to the standard armament configuration when additional miniguns arrived.

The AC-47 initially used SUU-11/A gun pods that were installed on locally fabricated mounts for the gunship application. Emerson Electric eventually developed the MXU-470/A to replace the gun pods, which were also used on subsequent gunships.

Miniguns at the ready

Flare canister

In August 1964, years of fixed-wing gunship experimentation reached a new peak with Project Tailchaser under the direction of Capt. John C. Simons. This test involved the conversion of a single Convair C-131B to be capable of firing a single GAU-2/A Minigun at a downward angle out of the left side of the aircraft. Even crude grease pencil crosshairs were quickly discovered to enable a pilot flying in a pylon turn to hit a stationary area target with relative accuracy and ease. The Armament Development and Test Center tested the craft at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida, but lack of funding soon suspended the tests. In 1964, Capt. Ron W. Terry returned from temporary duty in Vietnam as part of an Air Force Systems Command team reviewing all aspects of air operations in counter-insurgency warfare, where he had noted the usefulness of C-47s and C-123s orbiting as flare ships during night attacks on fortified hamlets. He received permission to conduct a live-fire test using the C-131 and revived the side-firing gunship program.

Minigun in action

By October, Capt. Terry's team under Project Gunship provided a C-47D, which was converted to a similar standard as the Project Tailchaser aircraft and armed with three miniguns, which were initially mounted on locally fabricated mounts—essentially strapped gun pods intended for fixed-wing aircraft (SUU-11/A) onto a mount allowing them to be fired remotely out the port side. Captain Terry and a testing team arrived at Bien Hoa Air Base, South Vietnam, on 2 December 1964, with equipment needed to modify two C-47s. The first test aircraft (43-48579, a C-47B-5-DK mail courier converted to C-47D standard by removal of its superchargers) was ready by 11 December, the second by 15 December, and both were allocated to the 1st Air Commando Squadron for combat testing. The newly dubbed "FC-47" often operated under the radio call sign "Puff". Its primary mission involved protecting villages, hamlets, and personnel from mass attacks by VC guerrilla units.

Spooky in Vietnam

Puff's first significant success occurred on the night of 23–24 December 1964. An FC-47 arrived over the Special Forces outpost at Tranh Yend in the Mekong Delta just 37 minutes after an air support request, fired 4,500 rounds of ammunition, and broke the Viet Cong attack. The FC-47 was then called to support a second outpost at Trung Hung, about 20 miles away. The aircraft again blunted the VC attack and forced a retreat. Between 15 and 26 December, all the FC-47's 16 combat sorties were successful. On 8 February 1965, an FC-47 flying over the Bong Son area of Vietnam’s Central Highlands demonstrated its capabilities in the process of blunting a Viet Cong offensive. For over four hours, it fired 20,500 rounds into a Viet Cong hilltop position, killing an estimated 300 Viet Cong troops.

Twin Browning arrangement

Gatling Minigun replacement

The early gunship trials were so successful, the second aircraft was returned to the United States early in 1965 to provide crew training. In July 1965, Headquarters USAF ordered TAC to establish an AC-47 squadron. By November 1965, a total of five aircraft were operating with the 4th Air Commando Squadron, activated in August as the first operational unit, and by the end of 1965, a total of 26 had been converted. Training Detachment 8, 1st Air Commando Wing, was subsequently established at Forbes AFB, Kansas. In Operation Big Shoot, the 4th ACS in Vietnam grew to 20 AC-47s (16 aircraft plus four reserves for attrition).

Spooky inbound

The 4th ACS deployed to Tan Son Nhut Air Base, Vietnam, on 14 November 1965. Now using the call sign "Spooky", each of its three 7.62 mm miniguns could selectively fire either 50 or 100 rounds per second. It can be seen in action here. Cruising in an overhead left-hand orbit at 120 knots air speed at an altitude of 3,000 ft, the gunship could put a bullet or glowing red tracer (every fifth round) bullet into every square yard of a football field-sized target in potentially less than 10 seconds.[dubious – discuss] And, as long as its 45-flare and 24,000-round basic load of ammunition held out, it could do this intermittently while loitering over the target for hours.

On the ground with an early model Hercules C130 A (note the short nose)

In May 1966, the squadron moved north to Nha Trang Air Base to join the newly activated 14th Air Commando Wing. The 3rd Air Commando Squadron was activated at Nha Trang on 5 April 1968 as a second AC-47 squadron, with both squadrons re-designated as Special Operations Squadrons on 1 August 1968. Flights of both squadrons were stationed at bases throughout South Vietnam, and one flight of the 4th SOS served at Udorn Royal Thai Air Force Base with the 432nd Tactical Reconnaissance Wing. The superb work of the two AC-47 squadrons, each with 16 AC-47s flown by aircrews younger than the aircraft they flew, was undoubtedly a key contributor to the award of the Presidential Unit Citation to the 14th Air Commando Wing in June 1968.

One of the most publicized battles of the Vietnam War was the siege of Khe Sanh in early 1968, known as "Operation Niagara". More than 24,000 tactical and 2700 B-52 strikes dropped 110,000 tons of ordnance in attacks that averaged over 300 sorties per day. During the two and a half months of combat in that tiny area, fighters were in the air day and night. At night, AC-47 gunships kept up a constant chatter of fire against enemy troops. During darkness, AC-47 gunships provided illumination against enemy troops.

Gunships pouring fire onto the enemy

An open shutter shows how an eliptical fly path allowed massive fire-power

to be unleashed on a relatively small (ca 50 sq metre target)

The AC-47D gunship should not be confused with a small number of C-47s which were fitted with electronic equipment in the 1950s. Prior to 1962, these aircraft were designated AC-47D. When a new designation system was adopted in 1962, these became EC-47Ds. The original gunships had been designated FC-47D by the United States Air Force, but with protests from fighter pilots, this designation was changed to AC-47D during 1965. Of the 53 aircraft converted to AC-47 configuration, 41 served in Vietnam and 19 were lost to all causes, 12 in combat. Combat reports indicate that no village or hamlet under Spooky Squadron protection was ever lost, and a plethora of reports from civilians and military personnel were made about AC-47s coming to the rescue and saving their lives.

.jpg)

As the United States began Project Gunship II and Project Gunship III, many of the remaining AC-47Ds were transferred to the Vietnam Air Force, the Royal Lao Air Force, and to Cambodia, after Prince Sihanouk was deposed in a coup by General Lon Nol.

A1C John L. Levitow, an AC-47 loadmaster with the 3rd SOS, received the Medal of Honor for saving his aircraft, Spooky 71, from destruction on 24 February 1969 during a fire support mission at Long Binh. The aircraft was struck by an 82-mm mortar round that inflicted 3,500 shrapnel holes, wounding Levitow 40 times, but he used his body to jettison an armed magnesium flare, which ignited shortly after Levitow ejected it from the aircraft, allowing the AC-47 to return to base.

Demand for the Spooky was so high that availability of Miniguns became a problem, so four of the AC-47Ds were put together using a stockpile of old Browning 7.62 millimeter (0.30 caliber) machine guns found in a warehouse in California, with each aircraft carrying ten side-firing machine guns each.

About 47 AC-47Ds were produced, with 12 lost in combat, particularly as enemy air defenses improved. A more capable platform -- in particular equipped with sophisticated sensor system to permit it to perform "search and destroy" missions instead of simply performing fire support -- was obviously needed. The AC-47Ds were replaced by the Fairchild AC-119G Boxcar gunship, with an electronic sensor system, for fire support missions, with the search and destroy mission farmed out to the highly sophisticated and completely fearsome Lockheed AC-130A Hercules / Spectre gunship.

Other air forces

In 2006, Colombia started operating retrofitted AC-47s, where they are known by civilians as Avion Fantasma (ghost plane). They are successfully operated by the Colombian Air Force in counter-insurgency operations in conjunction with AH-60 Arpia helicopters (an armed variant of the UH-60) and Cessna A-37 Dragonflys against local illegally armed groups. These are five Basler BT-67s purchased by Colombia with .50 cal (12.7 mm) GAU-19/A machine guns slaved to a forward looking infrared (or FLIR) system. They also have the ability to carry bombs. At least one has been seen fitted with one GAU-19/A and a 20 mm cannon, most likely a French made M621. The BT-67 is a variant of the C-47/DC-3 modified by the Basler Corporation of Oshkosh, Wisconsin.

In 1970, the Indonesian Air Force converted a former civilian DC-3. The converted aircraft was armed with three .50 cal machine guns. During 1975, the Indonesian Air Force used its "AC-47" in the Indonesian invasion of East Timor to attack the city of Dili. Later, the aircraft was used in Indonesian military close air support missions in East Timor. A retirement date is unknown.

In December 1984 and January 1985, the United States supplied two AC-47D gunships to the El Salvador Air Force and trained aircrews to operate the system. The AC-47 gunship carried three .50 cal machine guns and could loiter and provide heavy firepower for army operations. As the FAS had long operated C-47s, it was easy for the United States to train pilots and crew to operate the aircraft as a weapons platform. By all accounts, the AC-47 soon became probably the most effective weapon in the FAS arsenal.

Variants of the AC-47 based on various iterations of the airframe including the BT-67, have been used by Laos, Cambodia, South Africa, El Salvador, and Rhodesia, to name just a few, and with a variety of weapons configurations including Gatling guns of numerous types, various medium and heavy machine guns, and larger auto cannon (South African "Dragon Daks" were known to fit 20 mm cannons). The Republic of China Air Force (Taiwanese Air Force) also converted some of its C-47s to gunships. These machines were armed with M2 machine guns.

.50 cal vs 20 mm rounds for comparison

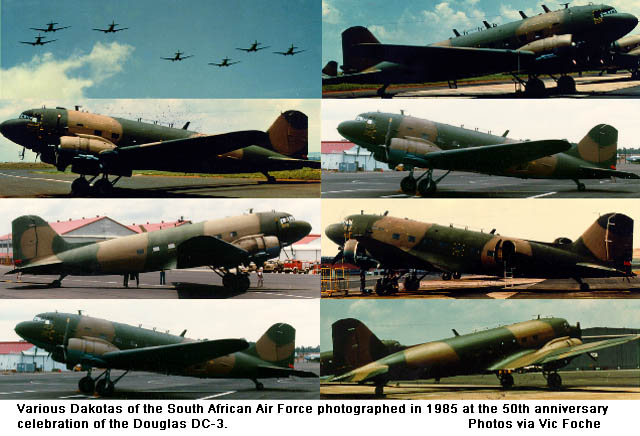

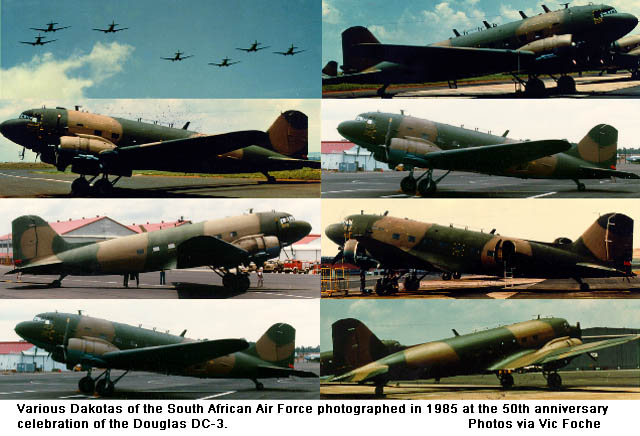

South African Air Force "Dragon Daks"

The Dak was often used for Paratroop drops

SAAF Gunships mounted either 20mm cannon or HMGs

Different arrangements were tested:

John Vorster, later Prime Minister, inspecting a twin HMG system

The single 20mm gun

SA Dragon Dak Gunner in action

_2.jpg)

.jpg)