The Airspeed 51 Horsa Glider

As part of the 70th Anniversary of the D-Day Normandy Landings our Wargames club is re-fighting the Sword Beach Landings of 1944.

This led me to research the history of the British 6th Airbourne and the Horsa Glider:

(Mostly from Wiki)

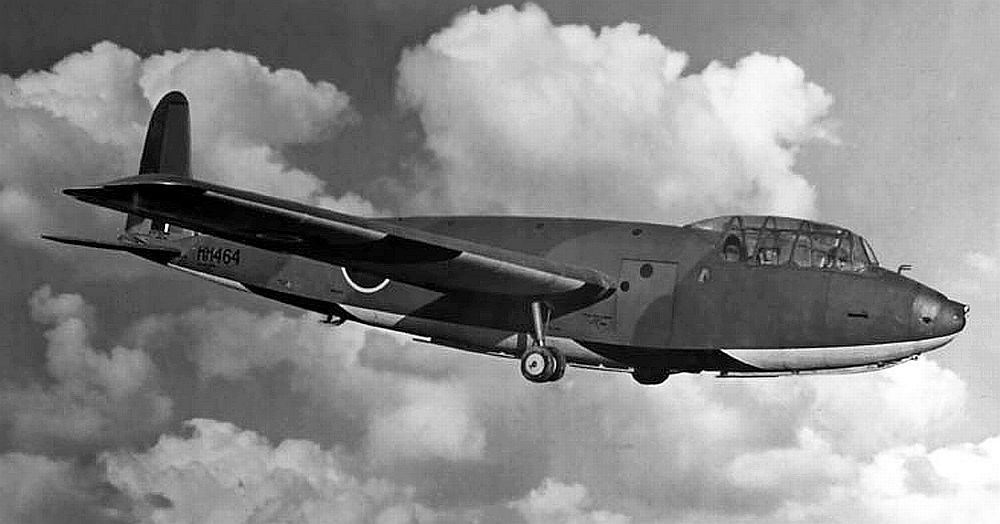

The Airspeed AS.51 Horsa was a British World War II troop-carrying glider built by Airspeed Limited and subcontractors and used for air assault by British and Allied armed forces. It was named after Horsa, the legendary 5th century conqueror of southern Britain.

The German military was a pioneer in the use of airborne operations, conducting several successful operations during the Battle of France in 1940, including the use of glider-borne troops in the Battle of Fort Eben-Emael and Crete. Impressed by the success of Germans airborne operations, the Allied governments decided to form their own airborne formations.This would eventually lead to the creation of two British airborne divisions, as well as a number of smaller units.

Tarrant Rushton Airfield, with gliders lined up

When the equipment for the airborne forces was under development, it was decided that gliders would be an integral component; used to transport troops and heavy equipment. The first glider to be designed and produced was the General Aircraft Hotspur. Several problems were found with the Hotspur's design, the primary one being that the glider did not carry sufficient troops.

Hotspur glider

Tactically it was believed that airborne troops should be landed in groups far larger than the eight the Hotspur could transport, and also the number of aircraft required to tow the gliders needed to carry larger groups would be impractical. There were also concerns that the gliders would have to be towed in tandem if used operationally, which would be extremely difficult during nighttime and through cloud formations. So the Hotspur was relegated to training duties, leading to the development of several other types of glider, including a 25-seater assault glider which became the Airspeed Horsa.

Initially it was planned that the Horsa would be used to transport paratroopers who would jump from doors installed on either side of the fuselage, and that the actual landing would be a secondary role; however the idea was soon dropped, and it was decided to simply have the glider land airborne troops. An initial order was placed for 400 of the gliders in February 1941, and it was estimated that Airspeed should be able to complete the order by July 1942. Enquiries were made into the possibility of a further 400 being produced in India for use by Indian airborne forces, but this was abandoned when it was discovered the required wood would have to be imported into India at a prohibitive cost. Five prototypes were ordered with Fairey Aircraft producing the first two prototypes for flight testing while Airspeed completed the remaining prototypes to be used in equipment and loading tests. The first prototype (DG597) towed by an Armstrong Whitworth Whitle, took flight on 12 September 1941 with George Errington at the controls.

Production of the Horsa commenced in early 1942, and by May some 2,345 had been ordered by the Army for use in future airborne operations. The glider was designed from the outset to be built in components with a series of 30 sub-assemblies required to complete the manufacturing process. Manufacturing was intended primarily to use wood-crafting facilities not needed for more urgent aviation production, and as a result production was spread across separate factories, which consequently limited the likely loss in case of German attack. he designer A. H. Tiltman said that the Horsa "went from the drawing board to the air in ten months, which was not too bad considering the drawings had to be made suitable for the furniture trade who were responsible for all production."

The initial 695 gliders were manufactured at Airspeed's factory in Christchurch, Hampshire, with subcontractors producing the remainder. These included Austin Motors and furniture manufacturers. The subcontractors did not have airfields to deliver the gliders from, and sent the sub-assemblies to RAF Maintenance Units for final assembly. 4000 to 5000 Horsas were built in all.

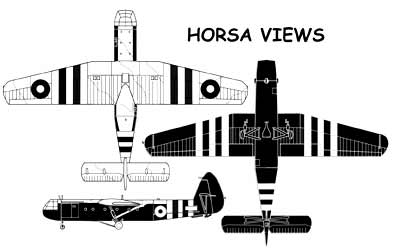

The Horsa Mark I had a wingspan of 88 feet (27 m) and a length of 67 feet (20 m), and when fully loaded weighed 15,250 pounds (6,920 kg).

The Horsa was considered sturdy and very manoeuvrable for a glider. Its design was based on a high-wing cantilever monoplane with wooden wings and a wooden semi mono-coque fuselage. The fuselage was built in three sections bolted together, the front section held the pilot's compartment and main freight loading door, the middle section was accommodation for troops or freight, the rear section supported the tail unit. It had a fixed tricycle landing gear and it was one of the first gliders equipped with a tricycle undercarriage for take off. On operational flights the main gear could be jettisoned and landing was then made on the castoring nose wheel and a sprung skid under the fuselage.

The wing carried large "barn door" flaps which, when lowered, made a steep, high rate-of-descent landing possible — allowing the pilots to land in constricted spaces. The pilot's compartment had two side-by-side seats and dual controls. Aft of the pilot's compartment was the freight loading door on the port side. The hinged door could also be used as a loading ramp. The main compartment could accommodate 15 troops on benches along the sides with another access door on the starboard side.

The fuselage joint at the rear end of the main section could be broken on landing to assist in rapid unloading of troops and equipment. Supply containers could also be fitted under the center section of the wing, three on each side.

The later AS 58 Horsa II had a hinged nose section, reinforced floor and double nose wheels to support the extra weight of vehicles. The tow cable was attached to the nose wheel strut, rather than the dual wing points of the Horsa I.

The Airborne Forces Experimental Establishment and 1st Airlanding Brigade began loading trials with the prototypes in March but immediately ran into problems. Staff attempted to fit a jeep into a prototype, only to be told by Airspeed personnel present that to do so would break the glider's loading ramp, as it had only been designed to hold a single motorbike. With this lesson learnt, 1st Airlanding Brigade subsequently began sending samples of all equipment required to go into Horsas to Airspeed, and a number of weeks were spent ascertaining the methods and modifications required to fit the equipment into a Horsa.

I also found this great video footage:

Last flight of the Assault Gliders

Operational history

With up to 30 troop seats, the Horsa was much bigger than the 13-troop American Waco CG-4A (known as the Hadrian by the British), and the 8-troop General Aircraft Hotspur glider which used for training duties only. Instead of troops, the AS 51 could carry a jeep or a 6 pounder anti tank gun.

The Horsa was first used operationally on the night of 19/20 November 1942 in the unsuccessful attack on the German Heavy Water Plant at Rjukan in Norway (Operation Freshman). The two Horsa gliders, each carrying 15 sappers, and one of the Halifax tug aircraft, crashed in Norway due to bad weather. All 23 survivors from the glider crashes were executed on the orders of Hitler, in a flagrant breach of the Geneva Convention which protects POWs from summary execution.

In preparation for further operational deployment, 30 Horsa gliders were air-towed by Halifax bombers from Great Britain to North Africa but three aircraft were lost in transit. On 10 July 1943, 27 surviving Horsas were used in Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily.

Large numbers (estimated at over 250) were subsequently used in Battle of Normandy; in the British Operation Tonga and American operations. The first units to land in France, during the Battle of Normandy, was a

coup de main force carried by 6 Horsas that captured Pegasus Bridge in Operation Deadstick, over the Caen canal, and a further bridge over the River Orne.

Ranville - note "Rommel's Asparagus" - anti glider posts

320 Horsas were used in the first lift and a further 296 Horsas were used in the second lift. Large numbers were also used for Operation Dragoon and Operation Market Garden, both in 1944, and Operation Varsity in March 1945; the final operation for the Horsa when 440 gliders carried soldiers of the 6th Airborne Division across the Rhine.

Horsas at Ranville

In operations, the Horsa was towed by various aircraft: four engined heavy bombers displaced from operational service such as the obsolete Short Stirling and Handley Page Halifax, the Armstrong Whitworth Albemarle and Armstrong Whitworth Whitley twin-engined bombers, as well as the US Douglas C-47 Skytrain/Dakota (not as often due to the weight of the glider, however in Operation Market Garden, a total of 1,336 C-47s along with 340 Stirlings were employed to tow 1,205 gliders,) and Curtiss C-46 Commando. They were towed with a harness that attached to points on both wings, and also carried an intercom between tug and glider. The glider pilots were usually from the Glider Pilot Regiment, part of the Army Air Corps, although Royal Air Force pilots were used on occasion.

British airborne troops guarding a road crossing, Horsas in background

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) acquired approximately 400 Horsas in a form of "reverse" Lend-Lease. A small number of Horsa Mk IIs were obtained by the Royal Canadian Air Force for post-Second World War evaluation at CFB Gimli, Manitoba. Three of these survivors were purchased as surplus in the early 1950s and ended up in Matlock, Manitoba where they were eventually scrapped. A small number of Horsas were also evaluated postwar in India. Due to low surplus prices in the UK, many were bought and converted to travel trailers and vacation cottages.

Horsa fuselage being converted into a "lovely little flat"

On 5 June 2004, as part of the 60th anniversary commemoration of D-Day, Prince Charles unveiled a replica Horsa on the site of the first landing at Pegasus Bridge, and talked with Jim Wallwork, the first pilot to land the aircraft on French soil during D-Day.

Replica at Pegasus Bridge

Ten replicas were built for use in the 1977 film A Bridge Too Far, mainly for static display and set-dressing, although one Horsa was modified to make a brief "hop" towed behind a Dakota at Deelen, the Netherlands. During the production, seven of the replicas were damaged in a wind storm; the contingent were repaired in time for use in the film. Five of the Horsa "film models" were destroyed during filming with the survivors sold as a lot to John Hawke, aircraft collector in the UK. Another mock-up for close-up work came into the possession of the Ridgeway Military & Aviation Research Group and is stored at Welford, Berkshire.

Variants

AS.51 Horsa I

Production glider with cable attachment points at upper attachment points of main landing gear.

AS.52 Horsa

Bomb-carrying Horsa; project cancelled prior to design/production

AS.53 Horsa

further development of the Horsa not taken up.

AS.58 Horsa II

Development of the Horsa I with hinged nose, to allow direct loading and unloading of equipment, twin nose wheel and cable attachment on nose wheel strut.

Interior

Operators

Belgium

Belgian Army - One aircraft only.

Canada

Royal Canadian Air Force

India

Indian Air Force

Portugal

Portuguese Air Force

Turkey

Turkish Air Force

United Kingdom

Army Air Corps

Glider Pilot Regiment

Royal Air Force

No. 670 Squadron RAF

United States

United States Army Air Forces

Survivors

An Airspeed Horsa Mark II (KJ351) is preserved at the Museum of Army Flying in Hampshire, England. The Assault Glider Trust is building a replica at RAF Shawbury using templates made from original components found scattered over various European battlefields and using plans supplied by BAE Systems (on the condition that the glider must not be flown).

Although there is some difference of opinion (now being researched), the replica at Pegasus Bridge is believed to incorporate a forward fuselage section retrieved from Cholsey, Oxfordshire, which had served as a dwelling for over 50 years. This relic was recovered from Cholsey around 2001 by the Mosquito Aircraft Museum, of London Colney, where it was stored until being transferred to Pegasus Bridge. The airframe is not believed to have seen active service.

Specifications (AS 51)

Data from British Warplanes of World War II

General characteristics

Crew: 2

Capacity: 25 troops (20-25 troops were the "standard" load)

Length: 67 ft 0 in (20.43 m)

Wingspan: 88 ft 0 in (26.83 m)

Height: 19 ft 6 in (5.95 m)

Wing area: 1,104 ft² (102.6 m²)

Empty weight: 8,370 lb (3,804 kg)

Loaded weight: 15,500 lb (7,045 kg)

Performance

Maximum speed: 150 mph on tow; 100 mph gliding (242 km/h / 160 km/h)

Wing loading: 14.0 lb/ft² (68.7 kg/m²)