SAAF Dakotas: WW2 and Berlin Air Bridge - The Early Days

The Douglas C-47 Skytrain or Dakota is a military transport aircraft that was developed from the Douglas DC-3 airliner. It was used extensively by the Allies during World War II and remained in front line operations through the 1950s with a few remaining in operation to this day.

WW2 SAAF and The Dak - The love affair starts:

The Shuttle Service was greatly expanded at the war’s end, the intention being the return of all South African troops by Christmas 1945. The Dakotas of 5 Wing were joined by Venturas withdrawn from coastal operations, modified as transports and put into service with 10 Wing at Pietersburg. These two units were assisted by 35 Sqn’s Sunderlands which were also fitted out as transports. Additional Dakotas were provided by 28 Sqn when it returned home from the war zone. By 25 January 1946 some 101 676 passengers had been carried.

The first SAAF Transport squadron in the Mediterranean - 28 Sqn - was formed in May 1943 operation from Tripoli and later Algiers. The second squadron - 44 Sqn - was established in March 1944 and operated from Cairo.

Both units operations Douglas Dakotas as standard equipment although a small number of Wellingtons, Ansons and Beech Expediters were also used.

In October 1945, 28 Sqn was absorbed into the Shuttle Service while 44 Sqn was disbanded in December 1945, and its Dakotas were returned to the RAF.

The first Douglas C-47 Dakota to serve with the SAAF was delivered to 44 Squadron in Cairo on 27 April 1944 and served with the squadron until 1992 when they were replaced by converted C-47TP versions.

WW2 North Africa/Med Camo SAAF C-47

SAAF Dak in East Africa

Troups enroute back to SA

Curiosity: Not a Dak, but a Captured JU 52 in SAAF colours

6856

Distinguished SAAF Dakota passengers:

Prof JLB Smith, Mr Lattimer and the Coelecanth

More about the Coelecanth: Old Four-Legs

The Berlin Air Lift

In 1948, the relations between the Western Allies and their Soviet counterparts had deteriorated to such a degree that the Soviets instituted a blockade on all rail, road and water canal links into West Berlin, situated 177 km (110 miles) into Soviet occupied Germany. The only way into Berlin was via three air corridors agreed upon at the Potsdam Conference in 1945.

It was decided to sustain the population of West Berlin by air, a feat that the Soviet Union had never anticipated. Thus, the Berlin airlift began on 24 June 1948.

The Berlin Wall being built

It was decided to sustain the population of West Berlin by air, a feat that the Soviet Union had never anticipated. Thus, the Berlin airlift began on 24 June 1948.

The SAAF supplied 20 aircrews for the Berlin Airlift, with the crews flying to Britain in Dakotas via east Africa, Egypt and Malta, a journey that took five days. They then joined the Royal Air Force in flying sorties into Berlin. The SAAF crews flew 2 500 sorties and carried a total of 8 333 tons of humanitarian aid while flying RAF Dakotas.

The sorties were flown from Lubeck in West Germany into RAF Gatow in West Berlin. In addition to this, civilian members in need of evacuation from occupied Berlin were carried on return trips to Lubeck, especially orphaned children who were placed with families in the West. It was here that modern air traffic control procedures were developed.

In all, during the 406 days of the Berlin Airlift, American, British and Commonwealth air crews carried out 300 000 flights and transported two million tons of supplies.

The Soviet blockade Berlin was lifted at one minute after midnight, on 12 May 1949.

Flights continued for some time, though, to build a comfortable surplus. By 24 July 1949, a three-month surplus was built-up, ensuring that the airlift could be re-started with ease if needed. The Berlin Airlift officially ended on 30 September 1949, after fifteen months.

There were four different means of entering Berlin from the West: by river and canal barges; road transport; the railways; and three air corridors which traversed the Soviet zone of occupation. While there was a written agreement with the Soviets regarding the use of the air corridors, nothing existed in writing about access to Berlin by any of the surface routes.

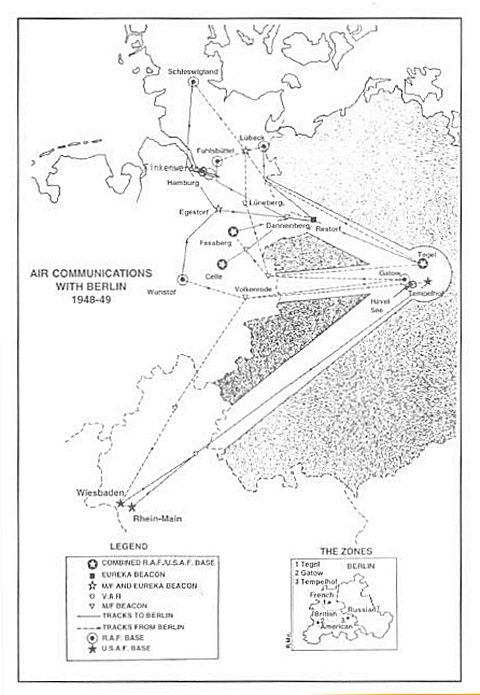

The central air control zone for Berlin covered a 20 mile (32 km) radius from the centre of the city and was under Four Power control. Most air routes into the city's existing airfields required some flying over the Soviet Sector of Berlin, as well as traversing well over 100 miles (160 km) of Soviet-occupied Germany. The North and Central Air Corridors came from the British zone of occupation and the South Air Corridor from the American zone.

Air communications with Berlin 1948-9

High resolution pdf version of map

The airlift begins

On 26 June, the United States Air Force and the Royal Air Force (RAF) began the Airlift, using a few DC3 Dakota aircraft (known in the US Air Force as the C47). These aeroplanes were capable of lifting only three tons on each flight and, on the first day of operations, only eighty tons of supplies arrived in Berlin. (The minimum amount required to sustain the city was initially calculated at 5 000 tons per day, 150 000 tons per month). Fortunately the Western powers in Berlin had begun stockpiling when the Soviets had commenced their harrassing tactics and therefore, when the blockade began, there were sufficient supplies in Berlin to last, on average, six to eight weeks.

Civilian rations were reduced to 1 000 calories per person per day

In the first month of the Airlift, a total of 70 241 tons of supplies was flown in to Berlin, just under half of the minimum needs of the city. By the end of the Airlift, the monthly total had risen to over 250 000 tons and this was probably one of the main contributing factors that convinced the Soviets that there was no future in maintaining the blockade. Compared with the amount of cargo which had to be moved, the capacity of the aircraft used in the Airlift necessitated a staggering number of flights. The Dakotas could carry only three tons, the Wayfarers five and a half tons and the Yorks, Skymasters, Hastings, Tudors and flying boats between eight and ten tons each. The aircrews themselves made a number of recommendations regarding the removal of standard fittings like oxygen equipment and dinghies, which were not considered necessary.

During the Airlift, the British and the Americans shared the three air corridors permitted under the original four-power agreement. Aircraft based in the British zone entered Berlin along the Northern Air Corridor and the American aircraft came in along the Southern Corridor. Aircraft leaving Berlin generally used the Central Corridor. However, some British aircraft that were based very far north in their zone, also left along the Northern Corridor. Since the Americans provided the largest number of the aircraft and their bases were the furthest from Berlin, the British made two of their airfields at Celle and Fassburg in the centre of Germany available for use by the Americans, thereby greatly reducing their flying time, and also allowed them to share the Northern Corridor.

Flying boats

A unique aircraft type, probably unknown to most people today, were the 'flying boats' which were also used during the Airlift. These aircraft were once a familiar sight to South Africans - operating on the air routes between the Union and Britain before and immediately after the Second World War. During the Airlift, flying boats operated from the marine base of Finkenwerder on the River Elbe on the outskirts of Hamburg to a base on the Havel See (Havel Lake) in Berlin. Apart from increasing the number of available aircraft, the flying boats were also used to carry most of the salt supplies, as their hulls had been treated against the corrosive effects of the salt water on which they normally landed.

(Land-based aircraft, lacking this anti-corrosion treatment, soon showed dangerous levels of corrosion due to salt cargo spillages and seepage. Having no night landing aids the flying boats operated only in the daytime from July until December 1948, when the Havel See became covered with ice. They did not resume operation after the Spring thaw.

Harrassment

Throughout the Airlift, the Soviets used a variety of means to harrass the air crews and to work on their fatigued nerves. For example, Soviet fighter aircraft played 'chicken' with the heavily-laden transports and carried out air-to-ground firing exercises with live ammunition very close to the corridors. The Soviet Army's anti-aircraft batteries also used live ammunition in exercises which took place as close as possible to the boundaries of the corridors and they flew barrage balloons alongside the corridors and held seeming endless conversations on the radio frequencies allocated to the Allied aircraft.

Apart from the fatigue caused by flying a number of operations daily under the most arduous of conditions, the crews lived in great discomfort. Their accommodation was either close to the airfields where the noise of the continuous flying operations made rest and sleep difficult, or they lived some distance away, requiring travelling between airfield and base which cut badly into their rest intervals. Furthermore, coal (the major cargo item) and flour produced prodigious quantities of dust which clogged flying controls and permeated the clothes of the air crews.

Berlin children

Conditions in occupied Germany were very severe and many people were reduced to begging. This was especially true of the children, who would follow the servicemen, calling out 'Got any gum, chum?' (probably the first words of English that they learned). A young American pilot, Lieutenant Gail Halvorsen, was sent on a familiarisation flight to Templehof and went on foot around the airfield to learn the approaches. He noticed a group of children who were standing at the fence close to the end of the runway and who were watching the aircraft coming in to land. Strangely, they did not beg when they saw him. Searching his pockets, Halvorsen found a few sticks of gum and a chocolate bar which he divided amongst some of them and promised that, if they were there the next day, he would drop some candy to them when he came in to land. When the children asked how they would know his aircraft, he told them that he would waggle his wings during his approach.

Returning to his base, Lt Halvorsen made several small parachutes out of a large supply of handkerchiefs which he had bought for a heavy cold. To each he attached a chocolate bar. On reaching Berlin the next morning he found the end of the runway crowded with children. His flight engineer dropped the little parachutes out of the flare chute and they were eagerly grabbed by the waiting children. This procedure was repeated every day and soon many Airlift crews joined in what became known as 'Operation Little Vittles'.

Der Schokoladenflieger

Halvorsen received two nicknames - 'Der Schokoladenflieger' (the chocolate pilot) and 'Uncle Wigglywings' - and German children sent him so much fan mail that his commanding officer had to provide him, a junior officer, with a German-speaking secretary to handle the replies. At Christmas Halvorsen received over 4 000 Christmas cards!

Halvorsen meeting the kids for the first time

When children from the Soviet Sector of Berlin wrote and complained that they were being left out, Halvorsen and his comrades started dropping chocolates over the eastern sector as well, until the Soviet authorities ordered this to cease. The trail of little parachutes eventually became a danger to approaching aircraft and an official 'dropping zone' was established over open ground in the Tiergarten Park.

The Air Police at the US bases began to offer minor offenders the choice of a fine or a contribution of chocolate for 'Operation Little Vittles'. Halvorsen himself was sent back to the USA on a public relations tour. He received thousands of handkerchiefs in the post, some with lace edges, drenched with perfume and with the donors' telephone numbers on them.

In May 1998, the US Air Force sent one of its few surviving C54 Skymaster aircraft to Berlin to take part in the 50th anniversary celebrations. Gail Halvorsen was a member of the crew for this flight.

Reducing weight

Various measures were taken to reduce the mass of the supplies which were being flown into Berlin during the Airlift. Known for their great love of potatoes, which they served up in a large variety of ways, the Berliners did not much like the dehydrated potato powder called 'Pom', with which they were supplied. However, as this cut down some 780 tons daily, the housewives of Berlin made the best of the situation with a saying: 'Better Pom than Frau komm!' As water makes up a quarter of the weight of bread, the ingredients were flown in and the bread was baked inside Berlin, while meat was de-boned to reduce its weight by 25%. In this way, Berlin's food requirements were successfully reduced from 2 000 tons to 1 000 tons a day.

The end of the blockade

The Soviets realised that they were neither going to be able to drive the Allies out of Berlin nor stop the Airlift. Tunner's Easter Parade demonstration had coincided with the signing of the North Atlantic Treaty which bound twelve countries together in a defence pact. In addition, the Allies had started turning back all trucks passing through the western zones of Germany, which were destined for the East, and so the Soviet zone was being starved of essential raw materials like coal and iron from the Ruhr.

On 12 May 1949, the blockade of Berlin was finally lifted. The Soviets tried to impose farther technical restrictions on movements from the West into Berlin but these were soon brushed aside by the Allies. In order to rebuild the stockpiles in West Berlin, the airlift continued for several months. British civil aircraft were finally withdrawn on 16 August and the RAF on 23 September, a few days after the SAAF crews had returned home.

Statistics

The statistics of the Airlift are as follows:

Estimated cost: US$ 200 million (For a reasonable present day comparison, this figure should be multiplied by at least 100)

Total number of aircraft used: 692

Total distance flown: 124 420 813 miles (equivalent to thirteen round trips to the moon or 4 000 times around the world)

Total number of flights: 277 804

Total tonnage into Berlin: 2 352 809

Coal: 1 586 530 tons (67%)

Food: 538 016 tons (23%)

Liquid fuel: 92 282 tons (4%)

Casualties: 65 men lost their lives -

- 31 Americans

8 RAF

11 British civilian crew

5 Germans

The last RAF flight

The last RAF flight from Lübeck landed at Gatow at 19.22 on 23 September 1949. The Dakota, appropriately carrying a load of coal, was inscribed with the following words:

'Positively the last load from Lübeck - 73 705 tons - Psalm 21 verse 11'. (In the King James version of the Bible, this verse reads: 'For they intended evil against thee, they imagined a mischevious device which they were not able to perform' - perhaps a suitable epitaph for the Berlin Airlift).

SOURCES

Collier, R, Bridge across the Sky (Macmillan, London, 1978)

Jackson, R, The Berlin Airlift (Patrick Stephens, Wellingborough, 1988)

Maree, B, 'The Berlin Airlift' in South African Panorama, December 1988, pp 14-18.

Morris, E, Blockade, Berlin & the Cold War (Military Book Society, London, 1973)

Personal reminiscences of Maj Gen Duncan Ralston; Col Peter MacGregor; and Capt Anthony Speir.

.jpg)