Avro Shackleton (Part 1)

Shackleton

Role

Maritime patrol aircraft

Manufacturer

Avro

Designer

Roy Chadwick, W.M. Taylor

First flight

9 March 1949

Introduction

April 1951

Retired

1990

Primary users

Royal Air Force

South African Air Force

Produced

1951–1958

Number built

185

Developed from Avro Lincoln

The Avro Shackleton was a British long-range maritime patrol aircraft for use by the Royal Air Force and the South African Air Force. It was developed by Avro from the Avro Lincoln bomber.

Avro Lincoln (Royal Australian Air Force)

It was originally used primarily in the anti-submarine warfare (ASW) and maritime patrol aircraft (MPA) roles, and was subsequently adapted for airborne early warning (AEW), search and rescue (SAR) and other roles from 1951 until 1990. It also served in the South African Air Force from 1957 to 1984. The type is named after the polar explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton.

The aircraft was designed by Roy Chadwick as the Avro Type 696.

It was based on the Lincoln bomber and Tudor airliner, both derivatives of the successful wartime Lancaster heavy bomber, one of Chadwick's earlier designs which was the then current ASW aircraft.

Avro Lincoln

The design took the Lincoln's centre wing and tail, Tudor outer wings and landing gear and a new wider and deeper fuselage; it was powered by four Rolls-Royce Merlin engines. It was initially referred to during development as the Lincoln ASR.3.

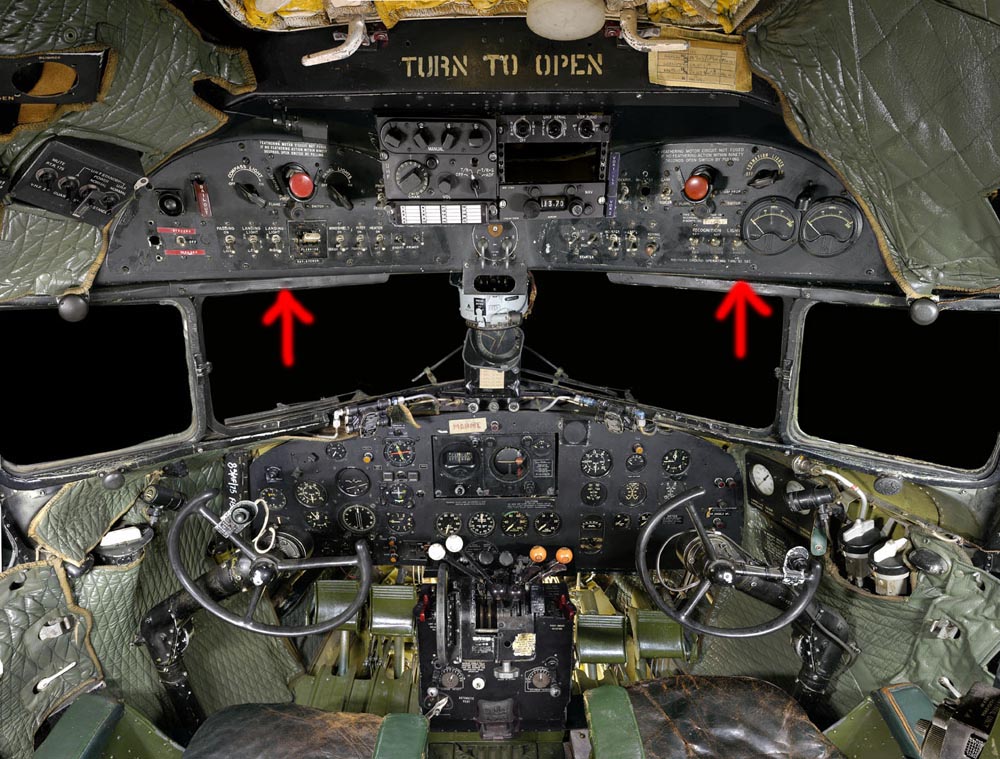

The design was accepted with Air Ministry specification R.5/46 written around it. The tail as adopted differed from the Lincoln. The Merlin engines were replaced with the larger, more powerful and slower-revving Rolls-Royce Griffons with 13 ft (4 m)-diameter contra-rotating propellers, which created a distinctive engine noise and added high-tone deafness to the hazards of the pilots due to their positioning in relation to the cockpit. The Griffons were necessary because of the greater weight and drag of the new aircraft over the Lincoln and they provided equivalent power to the Merlins but at lower engine speed, which made for greater fuel efficiency for the long periods in the denser air at low altitudes that the Shackleton was intended for when hunting submarines – known as "loitering" in RAF parlance – possibly several hours at around 500 feet or lower. This also made for less stress and wear, and hence reliability problems, for the engines.

If Merlins had been used they would have been needed to run at comparatively high power settings for hours at a time once a submarine contact had been detected. Using conventional propellers would have needed an increase in propeller diameter to absorb the increased power and torque of the Griffons, which was not possible due to limitations in undercarriage length and engine nacelle positioning of the Lincoln wing; the contra-rotating propellers gave greater blade area within the same overall propeller diameter.

When the Shackleton was being designed, the "Battle of the Atlantic" was still being fought and all possible submarine targets (German U-boats), were diesel-electric powered types that had very limited underwater endurance. The time underwater being limited by both the air available for the crew to breathe, and the battery power remaining to drive the submarine's underwater electric motors. While submerged, it was incapable of travelling any great distance away from where it was detected. Any aircraft could then call up friendly convoy escort surface ships who could subsequently deal with a submerged target in the normal way, (with depth charges aimed using their own ASDIC (sonar) sets). Hence for the Shackleton, endurance in terms of the length of time it could spend in the air – as opposed to all-out range – was of prime importance.

Once a submarine had been detected, it might be necessary for the aircraft to remain over the last sighted position of the submarine all day (or night), preventing it from surfacing and escaping at its higher surface speed. All the time the submarine was prevented from surfacing, the crew's breathable air was being exhausted, and the batteries were consuming power; eventually the submarine would be forced to come up for air. It could then be attacked by the aircraft itself, using its own air-dropped depth charges.

In the case of a submarine recharging its batteries and replenishing its air while submerged using a snorkel, this could be detected by the aircraft using ASV radar, and the submarine attacked as normal, with the added benefit that in visual conditions, location of the German snorkel mast made the submarine's underwater position obvious, aiding depth charge aiming.

The Avro design was ordered to Air Ministry specification R.5/46 as a replacement for the long-range Liberator.

Development

The first test flight of the prototype Shackleton GR.1, serial VW135, was made on 9 March 1949 from the manufacturer's airfield at Woodford, Cheshire in the hands of Avro's Chief Test Pilot J.H. "Jimmy" Orrell.[5] In the ASW role, the Shackleton carried both types of sonobuoy, Electronic warfare support measures - an Autolycus diesel fume detection system and for a short time an unreliable magnetic anomaly detector (MAD) system.

Shackleton MR1.

Weapons were nine bombs, or three torpedoes or depth-charges, and two 20 mm cannon in a Bristol dorsal turret. The GR.1 was later re-designated "Maritime Reconnaissance Mark I" – MR 1.

MR2

The MR 2 was an improved design incorporating feedback from operations and is considered by aficionados[citation needed] to be the definitive type. The radome was moved from the nose to a ventral position and was retractable, to improve all-round coverage and minimise the risk of bird-strikes. The radar was upgraded to ASV Mk 13.[6] Both the nose and tail section were lengthened, the tailplane was redesigned, the undercarriage was strengthened and twin-retractable tail wheels were fitted. The dorsal turret was initially retained, but was later removed from all aircraft after delivery. The prototype, VW 126, was modified as an aerodynamic prototype at the end of 1950 and first flew with the MR 2 modification on 19 July 1951. The aircraft was tested at Boscombe Down in August 1951 with particular attention to the changes to improve its ground handling, like the addition of toe-brakes and a lockable-rudder system. One production Mk 1 aircraft was modified on the line at Woodford with the Mk 2 changes and first flew on 17 June 1952. After trials were successful, it was decided to complete the last ten aircraft being built under the Mk 1 contract to MR 2 standard and further orders were placed for new aircraft. In order to keep pace with changing submarine threats, the Mk 2 force was progressively upgraded, with Phase I, II and III modifications introducing improved radar, weapons and other systems, as well as structural work to increase fatigue life. The modified aircraft would be to the same standard as the later MR 3 but without the additional Viper engines.

MR3

The Avro Type 716 Shackleton MR 3 was another redesign in response to crew suggestions. A new 'tricycle' undercarriage was introduced, the fuselage was increased in all main dimensions and had new wings with better ailerons and tip tanks. The weapons capability was also upgraded to include homing torpedoes and Mk 101 Lulu nuclear depth bombs. As a sop to the crews on 15-hour flights, the sound deadening was improved and a proper galley and sleeping space were included.

Due to these upgrades, the take-off weight of the RAF's MR 3s had risen by over 30,000 lb (13,600 kg) (Ph. III) and assistance from Armstrong Siddeley Viper Mk 203 turbojets was needed on take-off (JATO). This extra strain took a toll on the airframe, and flight life of the RAF MR 3s was so sufficiently reduced that they were outlived by the MR 2s.

SAAF MR 3 Head-on

Due to the arms embargo against South Africa, the SAAF's MR 3s never received these upgrades but were maintained independently by the SAAF.

The Avro Type 719 Shackleton IV, later known as the MR 4, was a projected variant using the extremely fuel-efficient Napier Nomad compound engine. The Shackleton IV was cancelled in 1955.

In 1967, ten MR 2s were modified with additional radar equipment as training aircraft to replace the T 4 in-service with the Maritime Operational Training Unit; they were known as T 2s.

Operational history

A total of 185 Shackletons were built from 1951 to 1958: around 12 are still believed to be intact, with one still airworthy (SAAF 1722 based at AFB Ysterplaat, Cape Town) but not flying due to a lack of qualified crew members.

Pelican 1722 at Ysterplaat AFB, Cape Town, SA

Royal Air Force

8 Sqn RAF flew the Shackleton AEW 2 from 1973 to 1991. This example was pictured on 26 June 1982.

Front line MR 1 aircraft were delivered to Coastal Command in April 1951, making their operational debut during the Suez Crisis.

All marks suffered from using the Griffon engines — thirsty for fuel and oil, noisy and temperamental with high-maintenance needs. The engines of MR 2s needed top overhauls in 1961 every 400 hours and went through a spate of ejecting spark plugs from their cylinder heads. It was not unusual to see an engine changed every day in a unit of six aircraft. They were constantly on the cusp of being replaced, but the potentially beneficial Napier Nomad re-engine did not happen.

RAF MR2 "Mr. McHenry"

Note the absence of tricycle undercarriage compared to MR3s

Shackletons were used in the Aden Protectorate during the Radfan Emergency against rebel tribesmen in Colonial Policing Operations. Leaflets would be dropped warning the tribes to vacate their properties which would then be bombed after they left.

The need to replace the Shackleton was first raised in the early 1960s. The arrival of the Hawker Siddeley Nimrod in 1969 was the end for the Shackleton in most roles but it continued as the main SAR aircraft until 1972. The intention to retire the aircraft was then thwarted by the need for AEW coverage in the North Sea and northern Atlantic following the phased withdrawal of the Fairey Gannet aircraft used in the AEW role by the Fleet Air Arm that began in the early 1970s. With a new design not due until the late 1970s, the existing AN/APS-20 radar was installed in modified Shackleton MR 2s, redesignated the AEW 2, as an interim measure from 1972. These were operated by No. 8 Sqn, based at RAF Lossiemouth. All 12 AEW aircraft were given names from The Magic Roundabout and The Herbs TV series.The development of the British Aerospace Nimrod AEW3 replacement dragged on and the eventual successor to the Shackleton did not arrive until the RAF finally abandoned the Nimrod AEW 3 and purchased the Boeing E-3 Sentry in 1991.

South African Air Force

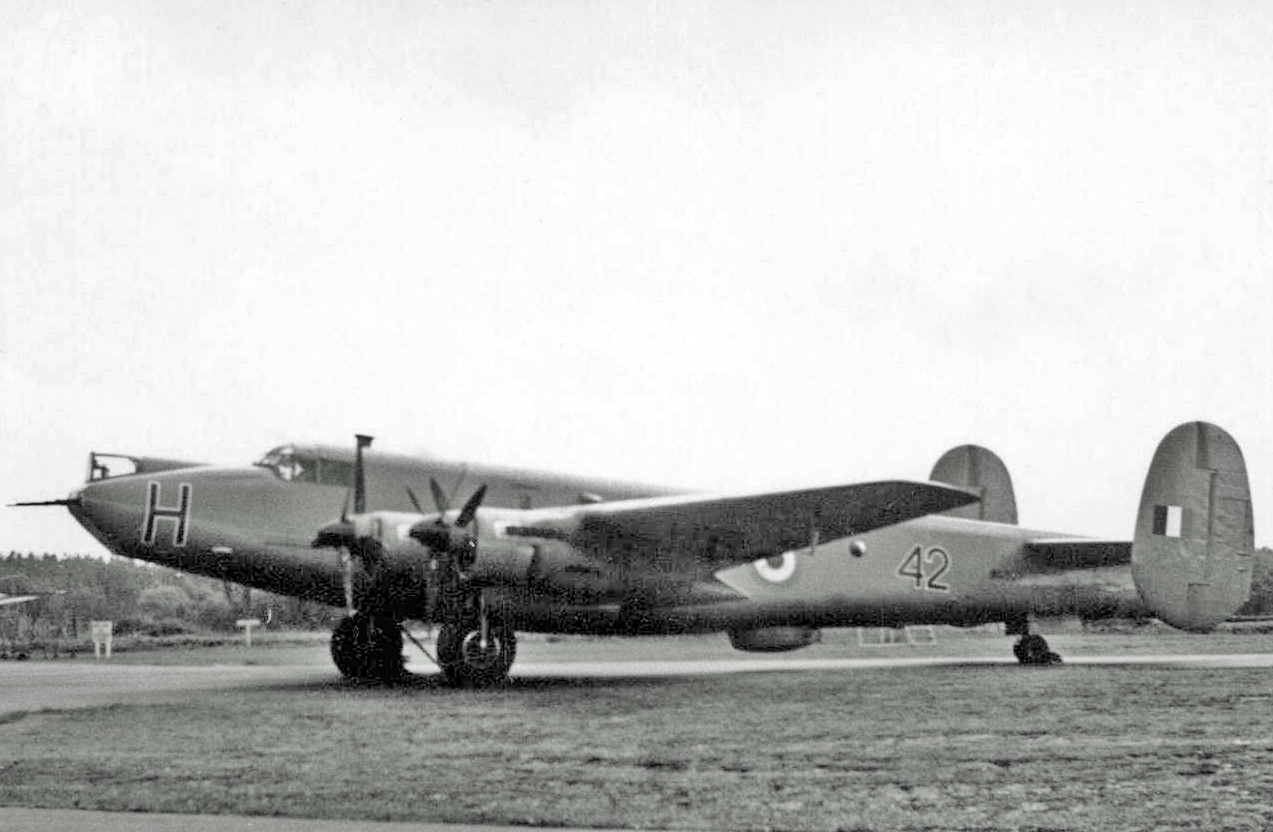

After evaluating four RAF MR 2's in 1953, the South African Air Force ordered eight aircraft to replace the Short Sunderland in maritime patrol duties. Some minor modifications were required for South African conditions and the resulting aircraft became the MR 3.

The Shackletons were serialled # 1716 - 1723. The first two were delivered to D.F. Malan Airport, Cape Town on 18 August 1957. They were followed by two more on 13 October and the remainder in February 1958. Delivered to the same basic standard as the RAF's Mk 3, they were assigned single letter codes between "J" and "Q" and operated by 35 Squadron SAAF.

Delivery in flying springbok roundel livery:

1716-J at delivery

Missions were mostly patrols of the sea lanes around the Cape of Good Hope, but some occasionally ranged as far as Antarctica. Most flew around 10,000 hours, with the only operational loss being 1718/"K", which crashed in the Wemmershoek mountain range in poor weather on 8 August 1963 with the loss of all 13 crew.

Due to the UK arms embargo against South Africa in protest at apartheid, spares for the Shackletons and their engines became difficult to obtain. A number of aircraft were re-sparred in South Africa, but the lack of engine spares and tyres, together with airframe fatigue, took a gradual toll. By November 1984, the fatigue lives of the aircraft had expired and the fleet was retired into storage.

Although the joke has been applied to several aircraft, the Shackleton has been described as "a hundred thousand rivets flying in close formation."

Avro 696 Shackleton prototypes

Avro 696

Three prototype Type 696s were ordered in May 1947 to meet specification R 5/46:

VW126

The first prototype which initially flew on 9 March 1949.

VW131

First flown on 2 September 1949.

VW135

First flown on 29 March 1950.

Avro 696 Shackleton MR 1 family

Shackleton MR 1

The first production model for the RAF. Dorsal Bristol turret with two 20 mm cannon, 29-built.

Shackleton MR1A

Variant powered by four Griffon 57A V12 piston engines, equipped with a chin mount radome; in service from April 1951, 47-built.

Shackleton T4

Navigation trainer conversion from MR 1 and MR 1As, removal of Bristol Type 17 mid-upper turret, addition of radar and radio positions for trainees and the addition of an ASV-21 radar, 16 conversions.

Avro 696 Shackleton MR 2 family

Shackleton MR 2

Version with longer nose and radome moved to the ventral position. Look-out position in tail. Dorsal turret and two more 20 mm cannons in nose. Twin retractable tail wheels. One aircraft, WB833, originally ordered as a MR 1 was built as a MR 2 prototype and first flew on 17 June 1952 it was followed by 69 production aircraft.

Shackleton T 2

Former MR 2s converted in the late 1960s as radar trainers, nose-cannon removed and radar trainee positions installed, ten conversions.

Shackleton AEW 2

Airborne early warning aircraft; MR 2s converted to take ex-Fairey Gannet AN/APS-20 airborne early warning radar, 12 conversions.

Avro 716 Shackleton MR 3 family

Shackleton MR 3

Maritime reconnaissance, anti-shipping aircraft. The tail wheel was replaced by a tricycle undercarriage configuration. Fitted with wingtip tanks. Eight exported to South Africa. Cannon in nose only. One prototype and 41 production aircraft.

Shackleton MR 3 Phase 1

The Phase 1 update introduced changes mainly to the internal equipment.

Shackleton MR 3 Phase 2

The Phase 2 update introduced ECM equipment and an improved High Frequency radio.

Shackleton MR 3 Phase 3

The third of three MR 3 modification phases including the addition of two Viper turbojet engines at the rear of the outboard engine nacelles to be used for assisted takeoff. The wing main spars had to be strengthened due to the additional engines. A new navigation system was also fitted and there were some modification to the internal arrangement, including a shorter crew rest area to give more room for the tactical positions.

Proposed designs

Shackleton MR 4

Project of new maritime reconnaissance version using Napier Nomad engines, none built.

Operators

South Africa

South African Air Force

35 Squadron SAAF received eight aircraft.

United Kingdom

Royal Aircraft Establishment

Royal Air Force (Coastal Command)

No. 8 Squadron RAF

No. 37 Squadron RAF

No. 38 Squadron RAF

No. 42 Squadron RAF

No. 120 Squadron RAF

No. 201 Squadron RAF

No. 203 Squadron RAF

No. 204 Squadron RAF

No. 205 Squadron RAF

No. 206 Squadron RAF

No. 210 Squadron RAF

No. 220 Squadron RAF

No. 224 Squadron RAF

No. 228 Squadron RAF

No. 240 Squadron RAF

No. 269 Squadron RAF

No. 236 Operational Conversion Unit, RAF

Maritime Operational Training Unit, RAF

Air Sea Warfare Development Unit, RAF

Survivors

Non-flying

SAAF 1722, commonly known as 'Pelican 22', is the only remaining airworthy Shackleton MR3.

The aircraft is owned and operated by the South African Air Force Museum based at AFB Ysterplaat. It was one of eight Shackletons operated by the South African Air Force from 1957 to 1984. Although it remains airworthy, it has been grounded by the Museum for safety and preservation reasons as well as a lack of qualified air and ground crew. Where possible, the engines are run-up once a month.

MR.2 WR963 (G-SKTN). In the care of the "Shackleton Preservation Trust", Live aircraft; under long term restoration to flight. Based at Coventry Airport, England.This aircraft also has running engines, and it is hoped it will be restored to flight status.

MR.3 WR982 on display at the Gatwick Aviation Museum, England. Engines can be run on this airframe.

Static display

SAAF 1716 ('Pelican 16'), crashed in the Sahara in 1994

(See separate post on this event)

MR 2C WL795 on display at RAF St. Mawgan, England. Due to be replaced by a Wessex helicopter during late 2013 due to its poor structural condition.

AEW 2 WR960 on display at the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester, England.

MR 3 WR971 fuselage sections on display at the Fenland & West Norfolk Aviation Museum, Wisbech, England and Norfolk & Suffolk Aviation Museum, Flixton, England.

MR 3 WR974 on display at the Gatwick Aviation Museum, England.

MR 3 WR977 on display at the Newark Air Museum, England.

MR 3 WR985 privately owned at Long Marston, England.

AEW 2 WL747 standing abandoned at the western end of runway 11/29 at Paphos Airport, Cyprus.

AEW 2 WL757 standing abandoned at the western end of runway 11/29 at Paphos Airport, Cyprus.

AEW 2 WL790 went on display at the Pima Air & Space Museum, Tucson Arizona USA in May 2013 after restoration.

SAAF 1716 ('Pelican 16') was restored to flight in 1994, but later that year, while on its way to the UK, it crash landed in the Sahara desert (22°37′50″N 13°14′15″W) after a double engine failure.The crash did not result in any casualties, but the aircraft was abandoned in the desert.

SAAF 1717 is on static display at the Transport museum in Stanger

SAAF 1720 (painted as 1717) used to be on static display at AFB Ysterplaat until 13 March 2013, when she was dismantled as scrap, following years of corrosion and no maintenance.

SAAF 1721 is on static display at the South African Air Force Museum in Swartkop.

SAAF 1723 is on static display at the Vic's Viking Garage, next to the N1 highway in Soweto, Johannesburg.

MR 3 XF700 abandoned and derelict, Nicosia, Cyprus

MR 3 XF708 on display at the Imperial War Museum, Duxford, England

T 4 WG11 nose on display at Flambards, Helston, Cornwall, England

Specifications

General characteristics

Crew: 10

Length: 87 ft 4 in (26.61 m)

Wingspan: 120 ft (36.58 m)

Height: 17 ft 6 in (5.33 m)

Wing area: 1,421 ft² (132 m²)

Airfoil: modified NACA 23018 at root, NACA 23012 at wingtip

Empty weight: 51,400 lb (23,300 kg)

Max. takeoff weight: 86,000 lb (39,000 kg

Fuel capacity: 4,258 imperial gallons (19,360 L)

Power plant: four × Rolls-Royce Griffon 57 liquid-cooled V12 engine, 1,960 hp (1,460 kW) each

Propellers: contra-rotating propeller, two per engine

Propeller diameter: 13 ft (4 m)

Performance

Maximum speed: 260 kn (300 mph, 480 km/h)

Range: 1,950 nmi (2,250 mi, 3,620 km)

Endurance: 14.6 hours

Service ceiling: 20,200 ft (6,200 m)

Max. wing loading: 61 lb/ft² (300 kg/m²)

Minimum power/mass: 91 hp/lb (150 W/kg))

Armament

Guns: 2 × 20 mm Hispano Mark V cannon in the nose

Bombs: 10,000 lb (4,536 kg) of bombs, torpedoes, mines, or conventional or nuclear depth charges, such as the Mk 101 Lulu

(From Wikipedia and various sources on the the Net, photos and data not my copyright: No infringement intended, just a fan blog. If you require more recognition of your photo/data, please just contact me. Happy to attribute/link or remove)

_2.jpg)