Wishing all my blog followers a Happy Xmas 2013 and Prosperity in 2014

A few Aircraft related festive photos:

Thursday, 26 December 2013

Sunday, 1 December 2013

Smaug on a Plane

Air New Zealand Unveils Smaug on a Boeing 777

Hobbit fans can finally see the most-anticipated character in the movie trilogy, the dragon Smaug.

While Smaug has previously been glimpsed in part, his full body has never been revealed.

Ahead of the premiere of the second part of the Hobbit trilogy, The Desolation of Smaug, Air New Zealand on Monday unveiled a 54-metre long image of the dragon on the sides of a Boeing 777-300.

Air New Zealand chief executive Christopher Luxon said the airline had worked with Weta Digital "to reveal their star to the world".

Advertisement

For the last premiere, the airline created another Hobbit-themed plane which carried stars to the Wellington premiere.

Director Sir Peter Jackson said he was proud to debut Smaug in New Zealand.

"To see Smaug fly off the big screen and into the skies like this is pretty exciting," he said.

The plane will fly to Los Angeles on Monday evening, arriving in time for the premiere on Tuesday.

Over the weekend, a giant eagle - a character from The Hobbit - was unveiled in the Wellington Airport terminal, alongside the character Gollum which was put up a year ago for the first premiere.

A further addition will be added at the airport.

Meanwhile, Peter Jackson and Middle-earth have popped up in a swanky Beverly Hills hotel.

As part of a Tourism New Zealand promotion, four replica sets from the movie were built inside the Beverly Hilton Hotel.

Jackson's three Lord of the Rings films and last year's first Hobbit film have created a tourism bonanza for New Zealand and Saturday's event was designed to attract another wave of American visitors.

Jackson shot all of the Lord of the Rings and Hobbit films in New Zealand and the Oscar winner joked he might even squeeze out a fourth Hobbit film.

''We have a few little corners of New Zealand that we're saving up for The Hobbit: Part Four,'' Jackson smiled.

''You never know.''

Jackson was joined at the event by The Hobbit's stars Martin Freeman, Richard Armitage, Evangeline Lilly, Luke Evans and Dean O'Gorman.

The sets at the Hilton included Laketown, shot at Lake Pukaki, Hidden Bay (Turoa, Ohakune), Forest River (Pelorus River) and Beorn's House (Paradise, Queenstown).

Video:

http://www.stuff.co.nz/business/industries/9465138/Hobbits-Smaug-debuts-on-Air-NZ-plane

Hobbit fans can finally see the most-anticipated character in the movie trilogy, the dragon Smaug.

While Smaug has previously been glimpsed in part, his full body has never been revealed.

Ahead of the premiere of the second part of the Hobbit trilogy, The Desolation of Smaug, Air New Zealand on Monday unveiled a 54-metre long image of the dragon on the sides of a Boeing 777-300.

Air New Zealand chief executive Christopher Luxon said the airline had worked with Weta Digital "to reveal their star to the world".

Advertisement

For the last premiere, the airline created another Hobbit-themed plane which carried stars to the Wellington premiere.

Director Sir Peter Jackson said he was proud to debut Smaug in New Zealand.

"To see Smaug fly off the big screen and into the skies like this is pretty exciting," he said.

The plane will fly to Los Angeles on Monday evening, arriving in time for the premiere on Tuesday.

Over the weekend, a giant eagle - a character from The Hobbit - was unveiled in the Wellington Airport terminal, alongside the character Gollum which was put up a year ago for the first premiere.

A further addition will be added at the airport.

Meanwhile, Peter Jackson and Middle-earth have popped up in a swanky Beverly Hills hotel.

As part of a Tourism New Zealand promotion, four replica sets from the movie were built inside the Beverly Hilton Hotel.

Jackson's three Lord of the Rings films and last year's first Hobbit film have created a tourism bonanza for New Zealand and Saturday's event was designed to attract another wave of American visitors.

Jackson shot all of the Lord of the Rings and Hobbit films in New Zealand and the Oscar winner joked he might even squeeze out a fourth Hobbit film.

''We have a few little corners of New Zealand that we're saving up for The Hobbit: Part Four,'' Jackson smiled.

''You never know.''

Jackson was joined at the event by The Hobbit's stars Martin Freeman, Richard Armitage, Evangeline Lilly, Luke Evans and Dean O'Gorman.

The sets at the Hilton included Laketown, shot at Lake Pukaki, Hidden Bay (Turoa, Ohakune), Forest River (Pelorus River) and Beorn's House (Paradise, Queenstown).

Video:

http://www.stuff.co.nz/business/industries/9465138/Hobbits-Smaug-debuts-on-Air-NZ-plane

Thursday, 21 November 2013

Dreamlifter 747 delivers Dreamliner parts to wrong airport

The pilot of a Boeing 747 jumbo jet mistakenly landed at a small Kansas airport not far from the Air Force base where it was supposed to deliver parts for the company's new 787 Dreamliner.

The 747 intended to touch down at McConnell Air Force Base in Wichita, which is next to a company that makes large sections of the 787.

Instead, the cargo flight landed 8 miles (13 kilometres) north, at the smaller Col. James Jabara Airport.

Hours later, the jet took off again and was expected to land at its original destination.

The plane landed in an area where there are three airports with similar runway configurations: the Air Force base, the Jabara airfield and a third facility in between called Beech Airport.

Boeing owns the plane, but it's operated by Atlas Air Worldwide Holdings, a New York-based cargo-hauler that also provides crews or planes to companies that need them.

Atlas Air spokeswoman Bonnie Rodney declined to answer questions and referred inquiries to Boeing.

"We are working with Atlas Air to determine the circumstances," Boeing said in a written statement.

The Federal Aviation Administration planned to investigate whether the pilot followed controllers' instructions or violated any federal regulations.

The pilot sounds confused in his exchanges with air traffic control, according to audio provided by LiveATC.net.

"We just landed at the other airport," the pilot tells controllers shortly after the landing.

Once the pilot says they're at the wrong airport, two different controllers jump in to confirm that the plane is safely on the ground and fully stopped.

The pilot and controllers then go back and forth trying to figure out which airport the plane is at. At one point, a controller reads to the pilot the co-ordinates where he sees the plane on radar. When the pilot reads the coordinates back, he mixes up "east" and "west."

"Sorry about that, couldn't read my handwriting," the pilot says.

A few moments later, the pilot says he thinks he knows where they are. He then asks how many airports there are to the south of McConnell. But the airports are north of McConnell.

"I'm sorry, I meant north," the pilot says when corrected. "I'm sorry. I'm looking at something else."

They finally agree on where the plane is after the pilot reports that a smaller plane, visible on the radar of air traffic control, has just flown overhead.

The modified 747 is one of a fleet of four that hauls parts around the world to make Boeing's 787 Dreamliner. The "Dreamlifter" is a 747-400 with its body expanded to hold whole fuselage sections and other large parts. If a regular 747 with its bulbous double-decker nose looks like a snake, the bulbous Dreamlifter looks like a snake that swallowed a rat.

According to flight-tracking service FlightAware, this particular DreamLifter has been shuttling between Kansas and Italy, where the centre fuselage section and part of the tail of the 787 are made.

Ad Feedback

McConnell is next to Spirit AeroSystems, which also does extensive 787 work. The nearly finished sections are then shipped to Boeing plants in Everett, Washington, and North Charleston, South Carolina for assembly into finished airplanes. Boeing is on track to make 10 of them per month by the end of this year.

Because 787 sections are built all over the world - including wings made in Japan - the Dreamlifters are crucial to the 787's construction. Boeing says the Dreamlifter cuts delivery time down to one day from as many as 30 days.

Although rare, landings by large aircraft at smaller airports have happened from time to time.

In July last year, a cargo plane bound for MacDill Air Force base in Tampa, Florida, landed without incident at the small Peter O Knight Airport nearby. An investigation blamed confusion identifying airports in the area, and base officials introduced an updated landing procedure to mitigate future problems.

The following month, a Silver Airways pilot making one of the Florida airline's first flights to Bridgeport, West Virginia, mistakenly landed his Saab 340 at a tiny airport in nearby Fairmont.

The pilot touched down safely on a runway that was just under 3200 feet (975 meters) long and 75 feet (23 metres) wide - normally considered too small for the passenger plane.

- AP

The 747 intended to touch down at McConnell Air Force Base in Wichita, which is next to a company that makes large sections of the 787.

Instead, the cargo flight landed 8 miles (13 kilometres) north, at the smaller Col. James Jabara Airport.

Hours later, the jet took off again and was expected to land at its original destination.

The plane landed in an area where there are three airports with similar runway configurations: the Air Force base, the Jabara airfield and a third facility in between called Beech Airport.

Boeing owns the plane, but it's operated by Atlas Air Worldwide Holdings, a New York-based cargo-hauler that also provides crews or planes to companies that need them.

Atlas Air spokeswoman Bonnie Rodney declined to answer questions and referred inquiries to Boeing.

"We are working with Atlas Air to determine the circumstances," Boeing said in a written statement.

The Federal Aviation Administration planned to investigate whether the pilot followed controllers' instructions or violated any federal regulations.

The pilot sounds confused in his exchanges with air traffic control, according to audio provided by LiveATC.net.

"We just landed at the other airport," the pilot tells controllers shortly after the landing.

Once the pilot says they're at the wrong airport, two different controllers jump in to confirm that the plane is safely on the ground and fully stopped.

The pilot and controllers then go back and forth trying to figure out which airport the plane is at. At one point, a controller reads to the pilot the co-ordinates where he sees the plane on radar. When the pilot reads the coordinates back, he mixes up "east" and "west."

"Sorry about that, couldn't read my handwriting," the pilot says.

A few moments later, the pilot says he thinks he knows where they are. He then asks how many airports there are to the south of McConnell. But the airports are north of McConnell.

"I'm sorry, I meant north," the pilot says when corrected. "I'm sorry. I'm looking at something else."

They finally agree on where the plane is after the pilot reports that a smaller plane, visible on the radar of air traffic control, has just flown overhead.

The modified 747 is one of a fleet of four that hauls parts around the world to make Boeing's 787 Dreamliner. The "Dreamlifter" is a 747-400 with its body expanded to hold whole fuselage sections and other large parts. If a regular 747 with its bulbous double-decker nose looks like a snake, the bulbous Dreamlifter looks like a snake that swallowed a rat.

According to flight-tracking service FlightAware, this particular DreamLifter has been shuttling between Kansas and Italy, where the centre fuselage section and part of the tail of the 787 are made.

Ad Feedback

McConnell is next to Spirit AeroSystems, which also does extensive 787 work. The nearly finished sections are then shipped to Boeing plants in Everett, Washington, and North Charleston, South Carolina for assembly into finished airplanes. Boeing is on track to make 10 of them per month by the end of this year.

Because 787 sections are built all over the world - including wings made in Japan - the Dreamlifters are crucial to the 787's construction. Boeing says the Dreamlifter cuts delivery time down to one day from as many as 30 days.

Although rare, landings by large aircraft at smaller airports have happened from time to time.

In July last year, a cargo plane bound for MacDill Air Force base in Tampa, Florida, landed without incident at the small Peter O Knight Airport nearby. An investigation blamed confusion identifying airports in the area, and base officials introduced an updated landing procedure to mitigate future problems.

The following month, a Silver Airways pilot making one of the Florida airline's first flights to Bridgeport, West Virginia, mistakenly landed his Saab 340 at a tiny airport in nearby Fairmont.

The pilot touched down safely on a runway that was just under 3200 feet (975 meters) long and 75 feet (23 metres) wide - normally considered too small for the passenger plane.

- AP

Tuesday, 5 November 2013

WW2 Today: First carrier action: USS Saratoga takes on Japanese Navy at Rabaul

USS Saratoga takes on Japanese Navy at Rabaul

After the attack on Rabaul harbour on the 2nd November a new threat developed for the landings on Bougainville. The Japanese had been careful to avoid exposing their ships to undue risk but they now felt compelled to bring in a force of seven heavy cruisers, one light cruiser and three destroyers. They were spotted refuelling in Rabaul and it was obvious they were set for an attack on the ships off Bougainville.

The U.S. had no capital ships near enough that would be able to challenge a force of this strength.

In early 1943, Rabaul had been distant from the fighting. However, the Allied grand strategy in the South West Pacific Area—Operation Cartwheel—aimed to isolate Rabaul and reduce it by air raids. Japanese ground forces were already retreating in New Guinea and in the Solomon Islands, abandoning Guadalcanal, Kolombangara, New Georgia and Vella Lavella.

Rabaul—on the island of New Britain—was one of two major ports in the Australian Territory of New Guinea. It was the main Japanese naval base for the Solomon Islands campaign and New Guinea campaign. Simpson Harbor—captured from Australian forces in February 1942—was known as "the Pearl Harbor of the South Pacific" and was well defended by 367 anti-aircraft guns and five airfields.

Lakunai and Vunakanau airfields were prewar Australian strips. Lakunai had an all-weather runway of sand and volcanic ash, and Vunakanau was surfaced with concrete. Rapopo—14 mi (12 nmi; 23 km) to the southeast—became operational in December 1942 with concrete runways and extensive support and maintenance facilities. Tobera—completed in August 1943 halfway between Vunakanau and Rapopo—also had concrete strips. The four dromes had 166 protected revetments for bombers and 265 for fighters, with additional unprotected dispersal parking areas. The fifth airfield protecting Rabaul was Borpop airfield, completed in December 1942 across the St. Georges Channel on New Ireland.

The anti-aircraft defenses were well coordinated by army and naval units. The army operated 192 of the 367 antiaircraft guns and the navy 175. The naval guns guarded Simpson Harbor and its shipping and the three airfields of Tobera, Lakunai, and Vunakanau. The army units defended Rapopo airfield, supply dumps and army installations; and assisted the navy in defending Simpson Harbor. An effective early warning radar system provided 90 mi (78 nmi; 140 km) coverage from Rabaul, and extended coverage with additional radars on New Britain, New Ireland, and at Buka. These sets provided from 30–60 minutes early warning of an attack.

Land-based air attacks

From 12 October 1943, as part of Operation Cartwheel, the U.S. Fifth Air Force, the Royal Australian Air Force and the Royal New Zealand Air Force—directed by the Allied air commander in the South West Pacific Area, General George Kenney—launched a sustained campaign of bombing against the airfields and port of Rabaul. After the first raid of 349 aircraft, bad weather blunted the effect of bombing, which saw only a single raid by 50 B-25 Mitchell medium bombers on 18 October. However sustained attacks resumed on 23 October and continued for six days, before culminating in the large raid of 2 November.

Nine squadrons of B-25s—totalling 72 bombers—and six squadrons of P-38 Lightning escorts attacked the anti-aircraft defenses and Simpson Harbor with minimum altitude strafing and bombing attacks. Eight B-25s were shot down by AAA or Japanese naval fighters, or crashed attempting to return to base. Among them was that of Major Raymond H. Wilkins of the 3rd Attack Group, posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his leadership. Nine of the 80 P-38s were also lost.

Carrier attacks

On Bouganville the Japanese had two airfields in the southern tip of the island, and another at the northernmost peninsula, with a fourth on Buki just across the northern passage. Instead of landing his forces near the Japanese airfields and taking them away against the bulk of the Japanese defenders, Admiral William Halsey landed his invasion force of 14,000 marines at Empress Augusta Bay, about halfway up the west coast of Bouganville. There he had his Seabees clear and build their own airfield. Two days after the landing Admiral Mineichi Koga sent a large cruiser force down from Japan to Rabaul in preparation for a night engagement against Halsey's screening force and supply ships in Empress Augusta Bay. The Japanese had been conserving their naval forces over the past year, but now committed a force of seven heavy cruisers, along with one light cruiser and four destroyers. At Rabaul the force refueled in preparation for the coming night battle.

Halsey had no surface forces anywhere near equivalent strength to oppose them. The battleships Washington and South Dakota and assorted cruisers had been transferred to the Central Pacific to support the upcoming invasion of Tarawa. Other than the destroyer screen for the transports, the only force Halsey had available were the carrier airgroups on Saratoga and Princeton. Rabaul was a heavily fortified port. With five airfields and extensive anti-aircraft batteries, the navy fliers considered it a hornet's nest. Up to that point in the war, other than the surprise raid at Pearl Harbor no mission against such a heavily defended target had ever been undertaken using carrier aircraft. It was a highly dangerous mission for the aircrews, and jeopardized the carriers as well. Halsey later said the threat the Japanese cruiser force at Rabaul posed to his landings at Bouganville was "the most desperate emergency that confronted me in my entire term as ComSoPac."

US Navy pilots Ensign Charles Miller, Lieutenant Henry Dearing, and Lieutenant Bus Alber walking toward their aircraft aboard USS Saratoga, 5 Nov 1943; note F6F fighter

With the landing in the balance, Halsey sent his two carriers under the command of Rear-Admiral Frederick Sherman to steam north through the night to get into range of Rabaul, then launch a daybreak raid on the base. Approaching behind the cover of a weather front, Sherman launched all 97 of his available aircraft against Rabaul. Aircraft from Barakoma Airfield on recently captured Vella Lavella were sent out to intercept the task group and provide some measure of air cover. Back at Rabaul, the carrier force drove their attack home. Under orders to make preference of damaging more ships rather than sinking a few, the air strike was a stunning success, inflicting damage on most units of the cruiser force and neutralizing it as a threat. The daybreak bombing of Rabaul was followed up an hour later with a raid by 27 B-24 Liberator heavy bombers of the Fifth Air Force, escorted by 58 P-38s. Most of the Japanese warships returned to Truk the next day to receive repairs and get them out of range of further Allied airstrikes. A serious threat had been neutralized.

F6 Hellcat

Saratoga was designed to carry 78 aircraft of various types, including 36 bombers, but these numbers increased once the Navy adopted the practice of tying up spare aircraft in the unused spaces at the top of the hangar. In 1936, her air group consisted of 18 Grumman F2F-1 and 18 Boeing F4B-4 fighters, plus an additional nine F2Fs in reserve. Offensive punch was provided by 20 Vought SBU Corsair dive bombers with 10 spare aircraft and 18 Great Lakes BG torpedo bombers with nine spares.

Miscellaneous aircraft included two Grumman JF Duck amphibians, plus one in reserve, and three active and one spare Vought O2U Corsair observation aircraft. This amounted to 79 aircraft, plus 30 spares.[ In early 1943-5, the ship carried 53 Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters and 17 Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bombers.

Damage to the Japanese forces at Rabaul were as follows:

Six cruisers damaged, four heavily. Atago was near-missed by three 500 lb (230 kg) bombs that caused severe damage and killed 22 crewmen, including her captain. Maya was hit by one bomb above one of her engine rooms, causing heavy damage and killing 70 crewmen. Mogami was hit by one 500 lb bomb and set afire, causing heavy damage and killing 19 crewmen.

Mogami

Takao was hit by two 500 lb bombs, causing heavy damage and killing 23 crewmen. Chikuma, was slightly damaged by several near-misses. Agano was near-missed by one bomb which damaged one anti-aircraft gun and killed one crewman. Three destroyers were also lightly damaged. Aircraft losses in the raid were light.

An additional carrier unit—Task Group 50.3 (TG 50.3) of the U.S. 5th Fleet—reached Halsey on 7 November. Commanded by Rear Adm. Alfred L. Montgomery, it consisted of the carriers Bunker Hill, Essex and Independence. Halsey used Montgomery's ships as well as TF 38 in a double carrier strike against Rabaul on 11 November. Sherman launched a strike from near Green Island, northwest of Bougainville, which attacked in bad weather at about 08:30. After its return, TF 38 retired to the south without being detected. Montgomery launched from the Solomon Sea 160 mi (140 nmi; 260 km) southeast of Rabaul.

Agano—which had remained at Rabaul after the 5 November strike—was torpedoed and heavily damaged in these attacks. The Japanese launched a series of counterattacks involving 120 aircraft against the U.S. carriers, but the force was intercepted and lost 35 planes without inflicting damage on Montgomery's ships.

Chikuma under attack

Monday, 14 October 2013

Pelican 16 Down : The sad story of a SAAF Shackleton (Part 3 of Shackleton MR3 in SAAF Service)

Pelican 16 Down:

The story of a grand old lady lost in the Sahara desert

Part 3 of the Shackleton MR3 in SAAF Service

SAAF Shackleton 1716, call-sign "Pelican 16" was the first Avro Shackleton built for the South African Air Force and the first to go into service upon its delivery on August 18th, 1957. Eventually joined by seven other aircraft, Pelican 16 formed part of the SAAF's 35 Squadron and for the next 27 years served as part of South Africa's Air Force patrolling the sea lanes around the Cape of Good Hope.

Side-lined by a combination of air frame fatigue and lack of spares due to apartheid-era embargoes on South Africa, Pelican 16 and the balance of the SAAF's Shackleton fleet were placed into storage by 1990.

Restored to flying condition by volunteers in 1994, Pelican 16 was offered to take part in a multi-stop air show tour in the UK and departed South Africa for England on July 12th, 1994, taking in the famous Farnborough Airshow. At the time she was the only airworthy Shackleton MR3 in the world.

Flown by a group of active SAAF pilots, Pelican 16 was operating over the Sahara desert in temperatures exceeding 38 deg C/100 deg F on the night of July 13th when her number 4 engine began to overheat from a coolant leak and had to be shut down. Moments later, a bolt connecting her two contra-rotating propellers in her no 3 engine failed, causing the assembly to overheat and melt and leaving the fuel-laden plane without any functional engines on its right wing.

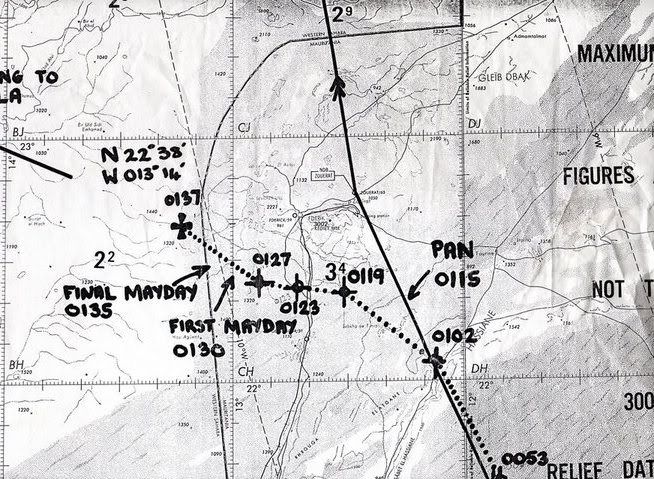

Left no option but a controlled ditching in the desert below, Pelican 16's pilots successfully belly-landed their aircraft on flat sands where it slid to a stop at this location. Though none of the crew were injured by the landing, all 19 men were miles from any assistance and in the middle of an active war zone. Through the next several days, the crew of Pelican 16 made their way to the safety of friendly forces and returned safely to South Africa.

The rescue

Today, the wreckage of Pelican 16 still remains where she came to a stop on the night of June 13th, 1994.

On the morning of 13 July 1994 the headline news in The Argus newspaper read “SAAF Plane Down in Desert”. Today, twelve years later and although she was found, Pelican 16 is for the records still “missing-in-action”; and remains at the crash site (click for panoramio map)

Enough has been written in the past on Pelican 16 and her last resting place in the Western Sahara when she hugged the sand with her belly on the night of 13 July 1994 after an emergency landing when her number 3 and 4 engines on her starboard side ignited and burned. A documentary by Andrew White told the story in great detail. The radio transmission that was made with military precision and efficiency are told to be used even today by the SA Air Force in their training as a text book example of how it should be done.

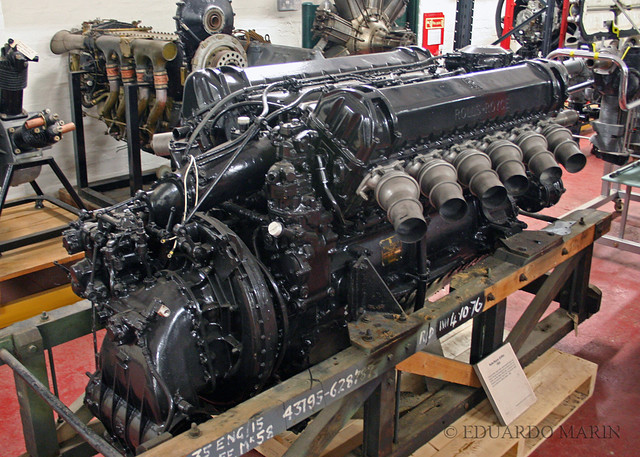

One can only begin to understand the legacy of, and the passion for this remarkable aircraft once you have heard for yourself the mighty roar of the four Rolls Royce Griffon engines. Everything else is only then put into perspective if you are lucky enough to touch the fuselage and ride the winds on the mighty wings of this Avro Shackleton MK3 called the “Pelican”.

This aircraft to some is bigger than religion and greater than fantasy…

Today a few survivors from the crash still believe that she should have been brought home years ago and others are of the opinion that it is significant to let her rest where she came to a halt.

Be as it may South Africa is still very fortunate to have Pelican 22 still in flying condion (albeit grounded) at Air Force Base Ysterplaat in Cape Town and to hear the four fabulous Griffons growl!

The crew who had to leave Pelican 16 behind:

Eric Pienaar (Pilot)

Peter Dagg (Co-Pilot)

John Balledon (2nd Co-Pilot)

Derick Page (Public Relations Coordinator)

Blake Vorster (Navigation Leader)

Horace (Hartog) Blok (2nd Navigator)

Frans Fourie (Flight Engineer)

Buks Bronkhorst (Aircraft Fitter)

JP van Zyl (Flight Engineer)

James Potgieter (Aircraft Fitter)

Lionel Ashbury (Telecom Operator)

Freddy Deutshmann (Radio Operator)

Chris Viviers (Radio Operator)

Pine Pienaar (Aircraft Electrician)

Spud Murphy (Radio Technician)

Ron Bussio (Museum Curator)

Gus Gusse (Aircraft Fitter)

Bobby Whitfield-Jones (Instrument Fitter)

Tony Adonis (Treasurer)

Lost in the desert sands: A first-hand account:

The South Africans Air Force crew who crash-landed this plane in the Sahara Desert were rescued with the help of a message dropped from the sky and a rebel movement.

This is all that's left of the SA Air Force Shackleton 1716, forever abandoned in the sand.

"No way will you ever hear that sound again," said mission commander Hartog "Horace" Blok.

He was reminiscing over the long-gone sound of the Shackleton's four Rolls Royce Griffon engines.

"The sound those engines make is just so unique. It's a sound that nothing can emulate, it's a beautiful sound."

Blok is now involved in aviation in the private sector.

These photographs were taken by United Nations officials who passed by the wreck recently.

In July 1994 the Shackleton, known as Pelican 16, had been refurbished in a huge project, and the team was flying from SA to England to take part in a series of airshows.

At the time The Star reported the aircraft was one of only two airworthy Shackletons left in the world, and had about 1 000 hours of airframe time left before being permanently grounded.

It had been used for maritime patrols off the South African coast until a few years before its last trip.

But en route to the English airshows, at night over the Sahara, the Shackleton had engine trouble and pilot Eric Pienaar had to crash land at 1.40am.

"It was pitch black. There was no horizon," remembered Blok.

"We just flew until we hit something.

"It's an anxiety attack that I never ever want to relive."

Driven by terror of fire, they fled from the plane and scattered.

Blok blew a whistle to get everyone together and, joining hands, they counted all 19 occupants.

Only two were slightly injured.

Still holding hands to stay together, one survivor led them in the Lord's Prayer - a ritual re-enacted at the survivors' union every year.

They had sent mayday messages shortly before crashing, but after that lost radio contact.

On the ground they set off a satellite-linked signal beacon - initially ignored by rescuers who disbelieved a signal from the Sahara.

At sunrise, they attracted the attention of a French naval plane from Morocco (inaccuate- Ex Dakar, Senegal - see erratum below-) by burning a tyre.

The French plane couldn't land, but eventually got help - by writing a note, shoving it into a plastic Coke bottle and dropping it on a UN team in two vehicles in the desert.

"One aircraft has crashed near your position - 19 persons on board.

"Position 015/10km from you. We try to contact you on frequency 1215 or 243 MHZ. GPS position 2238 north 01314 west," read the note.

Blok said the UN team fortunately included someone who spoke English, so could read the note.

Horrified at the prospect of 19 people mangled in an air crash, the UN team rushed to the scene.

"And there were the South Africans, beers in hand," said Blok.

The crash site was near Agwanit in the Western Sahara, for years in dispute between Morocco and the Polisaro Front, a Sahrawi rebel movement working for independence for the region.

The Shackleton survivors were helped by the Polisaro, even though South Africa did not recognise its government-in-exile until 10 years later.

The territory is still disputed.

"They took extremely good care of us," said Blok.

Within hours, the survivors had all been picked up.

"The last one of us left the crash site at 11.45am local time," Blok said.

The plane was written off as too difficult to salvage.

Now all that remains in the desert is the wreck of the grey- and-white plane, one of the last Shackletons to fly.

Update 25.03.2015

Erratum: Updated facts- The Search and Rescue operation that found Pelican 16 was operated by a French 22.F Squadron Breguet Br 1150 Atlantic 1 (22.F is based in Nimes, France)

The Atlatic 1 operated out of Dakar (Senegal) at the time; and not Morocco, as reported in my article.

Thank you to Sebastien Jouve, who was the radio operator on board the rescue flight for setting the record straight.

_edited-1.jpg)

Update 25.03.2015

Erratum: Updated facts- The Search and Rescue operation that found Pelican 16 was operated by a French 22.F Squadron Breguet Br 1150 Atlantic 1 (22.F is based in Nimes, France)

The Atlatic 1 operated out of Dakar (Senegal) at the time; and not Morocco, as reported in my article.

Thank you to Sebastien Jouve, who was the radio operator on board the rescue flight for setting the record straight.

_edited-1.jpg)

Thursday, 10 October 2013

Avro Shackleton MR3 in SAAF service (Part 2)

Avro Shackleton MR3 in SAAF service (Part 2)

35 Squadron Emblem

(Shaya Amanzi - From the Zulu: "Hit the Water")

To replace the Short Sunderland, the SAAF ordered eight Avro Shackleton MR Mk3 in 1954, and delivery took place in 1957. The SAAF operated (1957 to 1984) a total of eight Avro Shackleton Mk.3's with tail numbers 1716-1723.

One Shackleton was lost on operations when it crashed in the Wemmershoek (Stettynsberg) range of mountains during poor weather conditions on 8th August 1963 with the loss of life of all 13 crew:

All aircraft were deployed by 35 Squadron at AFB Ysterplaat Cape Town , after initially flying out of Congela , close to Durban harbour.

The Shackleton served as a Maritime Patrol Aircraft with both the SAAF and RAF and was later replaced in the SAAF by the C-47TP and Nimrod in RAF service. The SAAF however used only the Mk.3 variant without the Viper upgrade.

Procuring the Shackleton was a major step up from the previous use of Sunderlands and Catalinas and according to Wiki , even Harvards and Spitfires were used! Shackletons were used extensively until 23 November 1984 when it was officially withdrawn from service.

Shackleton 1716 was re-furbished to flying condition for the SAAF Museum, but had the unfortunate experience to crash land in the Sahara desert near the border with Mauritania on 13 July 1994 whilst on a flight to Great Britain to take part in a number of air shows. It suffered a number of engine failures and was forced to land in the dark, without any loss of life to the 19 crew on board. (See separate post on this)

Another Shackleton 1722 has been re-conditioned to flying status and flies as part of the SAAF Historical Flight in Cape Town.

Armament consisted of two 20-mm cannon in the nose, plus up to 10,000lb (4 536kg) of weapons in the underfuselage bay.

From the book Avro Shackleton by Barry Jones:

The SAAF's Shackleton strength was reduced by one in August 1963. 1718 had previously suffered a hydraulic failure,resulting in a wheels-up landing at D. F. Malan on 9 November 1959, but the

required repairs were carried out in record time, in order to get the aircraft back into service. On 8 August 1963 the aircraft had been engaged in joint exercises with the RAF and was on a return flight to Cape

Town. In gusting winds and severe icing conditions down to 3,000ft (l,000m), 1718 struck high ground before crashing into the Wemmershoek mountain range outside the town of Worcester, some 60

mile (96km) east of its destination. The crash occurred about 25.8 km (16 miles from the nearest town, Worcester, in the Stettynskloof valley between Paarl and Stellenbosch.

All thirteen crew members were killed in the tragedy, that was hard to accept by the squadron for some time. The aircraft had made a total of 777 flying hours during the six years since its acceptance by the SAAF

On the other side of the coin, two years later 1722 took part in an impressive display of search and rescue. Eight Buccaneer S.50s were in loose formation on their delivery flight to the SAAF when one, SAAF No.419, had a flame-out in both engines at high altitude, about 500 miles (800km) south of the Canary Islands. The two crew members,Captains Jooste and de Kerk, ejected while Major A. M. Muller, who was leading the formation, relayed their position. 1722 was scrambled, and only a couple of hours into the mission picked up the 'blips' from the downed airmen's SARAH beacons.

Coloured flares were fired by both the Shackleton crew and the survivors in the Atlantic, to verify visual contact by all concerned.Another MRJ, 1721, was drafted into what was no longer a search, but a rescue

operation and two sets of Lindholme Gear were dropped to the Buccaneer crew.

The Dutch liner Randfontein was in the area and 1722 guided it to the rescue location, where a successful transfer from life raft to luxury was made. 1722, captained by Major Pat Conway, had flown nearly eighteen

hours on the AR mission, which had been undertaken as a text-book operation.

In 1971, the treacherous currents around the Cape of Good Hope claimed another victim. The 70,000 ton oil tanker Wafra ran aground on rocks off Cape Agulhas, the most southerly tip of the African continent.

With its 60,000-ton cargo of crude oil threatening to cause an ecological disaster for the area's wildlife, not to mention the renowned holiday resorts that were located around that part of the country, an ocean-going tug was called in to tow the stricken vessel off the rocks. Good seamanship by the tug's crew got the Wafra

clear of the reef with very little oil spillage and the tanker was towed some 200 miles (300km) out to sea. As the vessel was unsalvageable in her existing state and there was no chance of transferring her cargo to another tanker, the SAAF was briefed to sink her, with the added instruction that, if possible, the ship's internal structure was not to be ruptured, so that she could take her cargo with her when she sank.

No. 24 Squadron's Buccaneer S.50s, armed with a pair of Nord AS-30 air-to ground missiles under each wing, carried out two sorties against the vessel, under the guidance of No. 35 Squadron, but the tanker remained intact. Consequently,MR.3s were called into action and a salvo of depth charges dropped alongside the Wafra had the desired effect. She sank onto the Agulhas Plateau, 2,300ft (700m) below the turbulent meeting place of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, complete with her crude oil.

At least two SAAF MRJs are known to have returned to the UK. 1719 arrived on 25 February 1963 for a six-week training exercise with Coastal Command and it arrived back at D. F Malan on 1 April. The

following year, 1722 touched down at BalIykelly on 28 June, for a four-week course at the JASS, returning to Cape Town on 30 July 1964.

After the loss of 1718, the seven surviving MR.3s were all progressively modified to Phase III standard by Hawker Siddeley CWPs, except that the Armstrong Siddeley Viper jet boost (JATO) engines was never installed in any of the South African aircraft. The bases used by No. 35 squadron were deemed to be large

enough to get even a fully laden MRJ airborne. The Phase III modifications were implemented before the arms embargo and the full ECM suit was installed in all seven aircraft, so that they approximated to the

RAF's final MR.3 condition, apart from the Viper JATO.

Wing re-sparring was carried out on at least two aircraft, 1716 being out of service for the work between March 1973 and April 1976. Re-sparring on 1717 took a lot less time - no doubt the engineers had

learned from the work on 1716 - the squadron being without the aircraft from September 1975 to October 1977. At least two other aircraft, besides 1718 and 1723 already mentioned, had undercarriage

problems on landing. 1722's nose wheel refused to lock down on 7 June 1960 and the aircraft landed on a foam laid down at Langebaanweg, the nose-wheel assembly collapsing on contact with the runway. Two years later, on 10 September 1962, 1721 had to make a wheels-up landingat Ysterplaat, but the damage sustained was repaired in a comparatively short time.

One other mishap to the SAAF MRJ fleet occurred on 18 September 196 I, when 1720 was undertaking asymmetric landing practice. The pilot undershot the runway at D. F Malan and the aircraft was extensively

damaged. Rather than dismantling 1720 and taking it away for repair, a hangar was constructed around it for the work to be carried out where it was.

The arms embargo certainly had a detrimental affect on the SAAF's MR.3s, and the two re-sparrings already mentioned were quite an engineering accomplishment on the part of their maintenance engineers. Engine spares were impossible to obtain, as were new tyres and electronic replacements so, in November 1984, the Shackleton was officially withdrawn as an operational aircraft in the SAAF.

1723 had expended its fatigue life several years prior to this and had been grounded since 22 November 1977. It was stored in the open at Ysterplaat, until being purchased by Vic de Villiers, who acquired the aircraft via a triple deal involving both the South African Airways Museum and the SAAF Museum. De Villiers gave the airways museum Vickers Viking ZS-DKH, which he had held for many years, and

they let the SAAF Museum have a Lockheed Ventura. The SAAF completed the convoluted agreement by selling 1723 to de Villiers, who mounted it on the roof of his 'Vic's Viking Garage' on the Johannesburg

to Vereeniging road. For many years it remained in its service colours, but without national markings. However, by 1994,commercial advertising had taken over and the aircraft was repainted a vivid red,

over which' Coca Cola' logos were liberally displayed. A sign that is mounted beside the aircraft, incorrectly said 'World War Two Shackleton'; today this has been edited and the word 'Two' has gone, although

the legend is still inaccurate.

On 24 April 1978, five months after 1723 was grounded, 1719 followed suit and it too was stored in the open at Ysterplaat to begin with. Later the aircraft was moved on it own wheels to an airfield at Stellenbosch, in the South African wine region. Finally, in 1991, 1719 was moved, to the

Cape Town Waterfront complex, where it is displayed today.

1720 had reached the end of its fatigue life by 10 March 1983, so it was grounded.

It had been planned to mount the aircraft a the gate guardian at Ysterplaat, but someone 'pulled rank' and instead it was positioned outside the Warrant Officer's Club. For a reason that cannot be ascertained,

it was repainted to represent '1719', complete with the individual code 'L'. Maybe it was hoped to frustrate future aviation historians, but today the aircraft's proper identity has been restored.

In 1984,1717 too was grounded; it had only been kept flying to that date by courtesy of a technical team that ascended the Wemmershoek Mountains to where the wreckage of 1718 lay, in order to retrieve serviceable parts that could be used on 1717. After open-air storage at Ysterplaat, the aircraft was dismantled to be taken by sea to Durban. From there, in October 1987,it went by road to Midmar Dam and was reassembled for static display at the Natal Park Board Museum.

The nostalgia of the Shackleton' retirement was not lost on the SAAF and on 23 November 1984 the surviving trio of airworthy MRJ ,1716,1721 and 1722, took part in a ceremonial flypast at D. F. Malan

Airport. Twelve growling Griffons was quite a farewell note! Two weeks after the ceremony, 1716 and 1721 were flown to the AAF Museum at Swartkop, while 1722 was retained in ground-running condition

by No. 35 Squadron for the museum.

In November 1991, the aircraft was flown to Ysterplaat, which, by then, had developed into the second largest military aviation museum in South Africa.

1963 ACCIDENT SUMMARY ANALYSIS

Occurrence Date: 8 August 1963

Aircraft Involved: one Avro MR. Mk 3 Shackleton (serial 1718)

Aircrew & Aircraft Home Unit: 35 Squadron at DF Malan International Airport

Aircraft Damage Classification: Category IIIa

Accident Root Cause: human error (pilot error)

Total Human Involvement: 13

Total On-Board Human Involvement: 13

Total Human Attrition: 13 killed

Identity of Deceased:

Pilot, Capt Thomas Howard Silvertsen (P22051) attested in the SAAF 01/04/48

co-pilot, 2/Lt Charles Alwyn du Plooy (P1/48842/1) attested in the SAAF 25/01/61

3rd pilot, Capt Jaques Guillaume Labuchagne (P21805) attested in the SAAF 04/02/53

navigator, Lt Abraham Gert Willem Coetzee (P20965) attested in the SAAF 28/01/57

2nd navigator, 2/Lt George James Smith (P1/24862) attested in the SAAF 23/03/60

3rd navigator, CO Derek Ian Strauss (P50506) attested in the SAAF 07/01/63

flight engineer, WO2 Sydney Shields Scully (P4895) attested in the SAAF 01/09/36

2nd flight engineer, L/Cpl Marthienus Christoffel Vorster (P2/20554) attested in the SAAF 01/04/58

signals leader, Sgt David Hope Sheasby (P17877) attested in the SAAF 03/03/55

radio operator, L/Cpl Charl Paul Viljoen (P20356) attested in the SAAF 01/06/55

2nd radio operator, L/Cpl Matthys Johannes Taljaard (P17993) attested in the SAAF 06/03/57

3rd radio operator, L/Cpl Michel Adolf Brodreiss (P23845) attested in the SAAF 01/12/59

4th radio operator, A/M Johannes Chamberlain (P50083) attested in the SAAF 01/07/62

Although 35 Squadron was based at the military section of DF Malan International Airport in Cape Town, the unit's headquarters was at nearby Air Force Station (AFS) Ysterplaat and it was at this latter facility that the flight crew of Shackleton 1718 received a full briefing at 12H30 on August 8, 1963. During this briefing, the Operations Officer on duty advised the Shackleton aircrew to head out over False Bay after take-off and to transit seawards towards the exercise area. He warned them that the direct overland route to Port Elizabeth should be avoided due to anticipated high icing levels on this route.

Forecast weather for the route over False Bay and then southwards was poor. Heavy icing conditions could be expected between 1 220 and 1 829 m ( 4,000 and 6,000 ft) above mean sea level (AMSL) and consequently the flight crew were further briefed that Maritime Group had granted them special clearance to transit to the exercise area under 915 m (3,000 ft) AMSL. A 244 m (800 ft) AMSL cloud base would exist with tops up to 6 707 m (22,000 ft). Heavy air turbulence could be expected with cumulonimbus clouds, hail and heavy rain throughout. Surface wind was 42 km/h (26 mph) at 340? and 92 km/h (57 mph) at 340? and 1 524 m (5,000 ft).

Even though the forecast weather over the eastern overland route was no better, at least the seaward route would eliminate the risk of the aircraft accidentally flying into high ground in the conditions of much reduced visibility. The aircraft commander, Captain (Capt) TH Silvertsen , when giving his own briefing, confirmed his route as south over False Bay and then seawards towards the exercise area. The flight had been authorised by Maritime Group to provide the Shackleton crew with training in the radar detection of a submarine. No special instructions were issued.

Shackleton 1718 was fully serviceable for flight even though the compasses had not been swung on their normal expiry date of July 19, 1963. Maritime Group gave authorisation for a month's extension provided that no major part of the aircraft was replaced. The compasses were therefore considered serviceable.

The Flight Office at Ysterplaat was uncomfortable about the weather conditions and telephoned the Maritime Group Operations Centre thrice prior to the departure of the Shackleton, in an effort to get the flight cancelled, but this request was not forthcoming.

Just minutes before take-off, Capt Silvertsen, notwithstanding his briefing instructions, informed Air Traffic Control (ATC) that he would climb to 2 896 m (9,500 ft) AMSL and head overland towards Port Elizabeth.

The aircraft lifted off Runway 34 at 15H06 and turned right on 350? for the climb out. Moments later, ATC informed the commander to come to 330? so as to safely avoid Tiger Mountain. Capt Silvertsen acknowledged this transmission and did accordingly. After the lapse of about a minute, he requested clearance to resume his original course of 350?. This was the last radio transmission received from Shackleton 1718.

At about 15H20 the radar technician at DF Malan requested permission to deactivate the radar for about ten minutes due to flooding of the radar installation on account of the heavy rain. This permission was granted, but before the radar was deactivated, 1718's location was given as a distance on the radar screen of about 40 km (25 miles) on a course of 100?. The ground course was about 145?.

Although the evidence suggested that the airplane had crashed, most likely in the Stettynskloof/Wemmershoek Mountains area, the adverse weather conditions, combined with the lateness of the hour, precluded any meaningful attempt at a search and rescue effort being mounted until the following day, August 9.

At 10H00 and again at 13H30 on August 9, helicopters were sent out to the Wemmershoek area to report on the weather, which remained completely adverse. Following a report of an aircraft having been heard, a further helicopter was despatched at 15H00 to search the mountains south of Simonstown. On August 10, another helicopter continued the search at Simonstown from 08H15, while a second aircraft was sent to report back on the weather in the Wemmershoek area. Here, the weather was still closed in, but hinted at the first signs of improvement. At 09H00 at aircraft was sent to fly high over the Wemmershoek Mountains to report on the cloud coverage. At 11H00 two aircraft continued a search in the same mountains and at 13H15 they were joined by a further pair of rotorcraft. The wreck was finally discovered from the air at 17H18 just over two days following the accident. It was evident from the almost complete destruction of the aircraft that nobody aboard could possibly have survived the crash.

The crash occurred about 25.8 km (16 miles from the nearest town, Worcester, in the Stettynskloof valley between Paarl and Stellenbosch. After inspecting the crash scene, the 35 Squadron Engineering Officer, Capt WJ Stiglingh decided to investigate the failures apparent on the port elevator and the upper section of the starboard rudder, both of which detached in flight, although the Board of Inquiry (BOI) officially convened to investigate the cause of the accident, was unable to establish which broke off first.

The section of the starboard rudder was found 1 620 m (5,314 ft) and the port elevator 1 250 m (4,100 ft) from the impact point. Following the disintegration of these two flight control surfaces, the aircraft would have been rendered uncontrollable. At this point (about 15H25) the pilot was heard to make his final radio transmission: “Mayday. Mayday,” but this was not recognised as such by the ATC. The timing of the transmission coincides exactly with the crash time.

At the same time that the starboard rudder and port elevator detached in flight, the port fuel tip tank also broke away removing a section of the port wing and both outer elevators. The outer most starboard elevator was found further forward than the impact point of the port tip tank. Clearly, it broke away shortly after the tip tank. The port elevator, which was complete, showed relatively little damage. Most of the damage sustained was consistent with it having fallen on to its inboard end and then on to some rocks. Signs were found, however, of excessive downward movement of this elevator to the extent that the hinges had damaged the steel spar, more so at the outboard hinge where the hinge arm had actually cut into the spar. It was official opinion that pilot applied force could not have caused this damage since the control column movement in restricted by stops strong enough to resist human force.

It is considered that at the time of the excessive downward movement of the elevator, the force, mainly due to leverage over the spar, was sufficient to cause failure of the hinge bolts in tension. Failure of the spar attachment upper lug clearly indicated that the outboard end of the elevator broke away first in a rearward direction. No evidence was found to suggest that this port elevator was attached to the airframe at the time of impact.

Examination of the starboard elevator indicated that its upward travel had been exceeded; this and other damage to this elevator being consistent with crash damage.

Regarding the section of the upper starboard rudder, the outboard skin at the break had failed in tension and the inboard skin was torn away from the front rearwards, this indicating that the broken off portion was first bent inwards and then backwards. Furthermore, apart from damage at the upper leading edge, which was inflicted when the rudder struck the ground, this portion of rudder was altogether undamaged. The rudder was probably detached from the aircraft before the point of impact.

As for the lower portion of the starboard rudder, failures on the outboard and inboard skins correspond to failure on the upper section. Damage on this section would appear to indicate that it did not strike the ground at the point of impact, but that it was flung forwards and carried further assisted by the strong winds prevailing at the time.

Considerable violence coupled with exceptionally strong winds and/or air turbulence was necessary to carry the port and starboard fin, port tailplane and several other pieces of empennage to their final positions. None of these parts, except the starboard fin, displayed any damage that could have occurred at the point if impact.

The port tailplane front spar had pulled out along its length, shearing all its rivets. Examination of the main impact zone indicated that the fuselage struck at right angles to the main mark down the slope and the sideways cartwheel or flick might have thrown empennage parts in to the air forward of, and to the right of, the impact area.

Examination of the point of impact of the port wingtip fuel tank indicated that the angle that the tank struck the ground was such that, had the tank been attached to the aircraft, the empennage should then have hit the ground. The tank was therefore most probably detached from the aircraft while still in the air. Positions of the No. 3 and 4 ailerons and part of the port wing support this reasoning.

The dump valves of both port and starboard tip tanks were found in the fully open position. As these valves are electro-mechanically driven, they were probably intentionally open and most likely before the port tip tank impact since this tank still had a considerable amount of fuel left over in it, judging by the flash fire area. The forward portion of the starboard tip tank, on the other hand, showed no signs of flash fire or explosion, indicating that its fuel content at the time of impact must have been low. The open dump valves appear to suggest that the pilot must have been busy dumping fuel in order to reduce the load on the airframe when it experienced the heavy turbulence and just before the aircraft began disintegrating. The aircraft weighed about 43 213 kg (95,242 lb) at the time of the accident.

In an attempt to reconstruct the events leading up to the crash, another Shackleton of the same weight and load as Shackleton 1718, took off from Runway 34 at DF Malan on August 22, 1963 to attempt to emulate as closely as possible the course and climb tempo of the stricken aircraft. Based on this emulation, it was ascertained that Shackleton 1718 was either at or very close to its intended cruise altitude of 2 896 m (9,500 ft) AMSL.

Instrument Flight Rules (IFR) flight had been authorised and the aircraft had been operating under IFR conditions at the time of its demise.

The Board was satisfied that the flight crew were under all circumstances both qualified and capable of performing the mission with which they had been tasked.

The accident occurred over State ground; property of the Department of Forestry. The terrain was unplanted, deforested and in its natural state. No claim could thus be made by the Department. There was no damage to private or other military property.

Shackleton 1718 was manufactured in August 1957. Although possessing a maximum take-off weight of 45 372 kg (100,000 lb), for its final flight it lifted off at 43 938 kg (96,840 lb). Since the aircraft was heavily laden with its maximum weight point close to the rearmost limit, the pilots would have experienced some instability in the yawing (left/right) plane.

The Board established that the impact speed of the aircraft was high and that this, combined with the resulting fire following the crash, caused almost complete destruction of the aircraft. There was no attempt by the crew to use parachutes and all aboard are assumed to have perished in the high G impact.

The Board established that the atrocious weather was a significant contributory factor in this accident. Wind was about 148 km/h (92 mph) due to the unstable air mass forming convection currents. Cloud cover extended from 305 m (1,000 ft) to 8 841 m (29,000 ft) AMSL with associated heavy precipitation. Due to the turbulence, the moist unstable air mass and low icing height resulted in unusually high icing conditions from 1 220 m to 1 829 m (4,000 ft-6,000 ft).

Air Force headquarters telephonically informed the Board that the maximum acceleration permitted on the Shackleton airframe was 2.4 G. It was thus theoretically possible to easily exceed this low limitation, especially under conditions of unusually high turbulence as in this case. Although it cannot be proved, it is not impossible that the pilot in control could have over controlled the aircraft on at least one occasion in response to the unusually heavy turbulence. This could have placed an additional load on the airframe.

It was considered a possibility that, due to the turbulence, the pilot found himself unwittingly between the mountain peaks and that either one wingtip or one of the tail surfaces skimmed the side of one of the mountains, the impact causing the aircraft to disintegrate in flight and causing the pilot to lose control. The Board, however, considered this scenario unlikely given the fact that the ATC heard the pilot's Mayday transmission clearly and the aircraft must have thus been flying above the mountain peaks under normal circumstances when the radio call was put out. Additionally, the fact that the dump valves were open does not correspond with a collision against a mountain.

The Board found Capt Silvertsen solely responsible for the accident. He displayed a complete lack of discipline by disobeying a direct order to rather route south over False Bay and instead routed over land, where the mountainous terrain exacerbated the already foul weather conditions. The aerodynamic effect of heavy icing, strong and turbulent winds, the heavy weight of the aircraft combined with the possible over control by the pilot in control, placed an unusually high loading on the airframe. This resulted in the airframe exceeding its design limits and initiated disintegration, leading to the loss of control and the consequent fatal crash. The accident was classed as an avoidable major flying accident.

All the evidence submitted by all the witnesses interviewed was considered credible by the Board.

Shackleton 1718 was delivered new to the SAAF valued at R 417 250.00. At the time of its demise it had completed 775.15 total airframe hours and, with depreciation, was valued with engines and propellers at R 266 109.45. The Rolls-Royce Griffon Mk 57A piston engines, like the airframe, were all classified as having sustained Category IIIa (write-off damage with no salvageable content). Engine numbers were 64411, 64412, 64416 and 64445.

This was the only Shackleton to be written off in 27 years of SAAF service from 1957 to 1984.

The Group Commander remarked that the ultimate load factor was 4 G. This figure suggests that the airframe was considerably stronger than the BOI was made to believe when they made their investigation. This information was, however, not available to the Board at the time.

The only flight crew member of the 13 that perished on board to have received any honours or awards was WO2 (Warrant Officer Class 2) Scully, recipient of the Africa Star with Clasp and the Union Medal (No. 285).

Individual Aircraft History:

1716 / J - c/n1526, first flight 29th March 1957, accepted at the Woodford Airfield by 35 Sqdn on the 16th May 1957, ferried to RAF St Mawgan for SAAF air-crew work-up exercises on the 21st May 1957, Departed for South Africa on the 13th August 1957, arrived Waterkloof on the 18th August 1957, Progressively modified up to Phase III standard. Wing re-sparring took place in South Africa, from March 1973 to April 1976. The aircraft took part in the retirement ceremony flypast at DF Malan airport, Cape Town, on the 23rd November 1984.

She was ferried from Cape Town to the SAAF Museum Swartkops on the 4th December 1984, with Capt Louis van Wyk as aircraft Captain. Restored to airworthy status in 1994, for planned attendance at a series of airshows in the UK. 1716 departed Cape Town International RW01 on the 8th July 1994, for the United Kingdom, routing via Libreville, Gabon, - Abidjan, Ivory Coast, - Lisbon, Portugal for intended entry into the UK via Brize Norton. Crashed 13th July 1994, in the Western Sahara Desert (22.38N, 03.14W) en-route to the UK.

Shackleton 1720 - painted as 1717 - which was on static display in front of the NCO's mess at

Ysterplaat AFB in Cape Town for many years, was sadly broken up on 12th March 2013.

Speculation has it that it was due to corrosion - it had been considered a safety hazard

1717 / O - c/n1527, first flight on the 6th May 1957, accepted at the Woodford Airfield by 35 Sqdn on the 16th May 1957, ferried to RAF St Mawgan for SAAF air-crew work-up exercises on the 21st May 1957, Departed for South Africa on the 13th August 1957, arrived Waterkloof on the 18th August 1957, from where 1716, 1717, & 1718 departed to Cape Town. The a/c was progressively modified up to Phase III standard. Wing re-sparring was done from September 1975 to October 1977. The aircraft was withdrawn from service & placed in storage at AFB Ysterplaat. During October 1987, she was dismantled & transported by sea to Durban, & then via road to the Midmar Dam, for static display at the Natal Parks Board transport museum. Financially the Natal Parks Board were unable to keep funding the museum, and all the exhibits were disposed of. With the subsequent closure of the Midlands Historic Village, where the aircraft was displayed, she was bought on auction by Mr Desai, a private businessman from Stanger in Kwazulu Natal. As of 2006, the airframe had been cut up for scrap, with only the engines remaining, potentially being sold to the UK.

1718 / K - c/n1528, first flight on the 13th May 1957, accepted at the Woodford Airfield by 35 Sqdn on the 16th May 1957, ferried to RAF St Mawgan for SAAF air-crew work-up exercises, Departed for South Africa on the 13th August 1957, and arrived Waterkloof on the 19th August 1957, from where 1716, 1717, & 1718 departed to Cape Town. The a/c had a wheels-up landing at DF Malan airport on the 9th November 1959, and was repaired during 1959-1960. She crashed in the Wemmershook mountains during poor weather, on the 8th August 1963. The aircraft was taking part in a CAPEX exercise, when severe icing caused loss of control, and the aircraft crashed inverted into a mountain valley, killing all 13 onboard. The crew were: Capt Thomas Howard Sivertsen , Capt Jaques Guillaume Labuchagne, Lt George James Smith, Lt Abraham Gert Willem Coetzee, CO Derek Ian Strauss, 2/Lt Charles Alwyn du Plooy, WOII Sydney Shields Scully, A/Cpl Charl Paul Viljoen, A/Cpl Marthienus Christoffel Vorster, T/A/Cpl Matthys Johannes Taljaard, A/Cpl Michel Adolf Brodreiss, F/Sgt David Hope Sheasby, Air Mech Johannes Chamberlain.

1719 / L - c/n1529, first flight on the 6th September 1957, accepted by 35 Sqdn in January 1958, departed for Cape Town on the 8th February 1958, arrived Cape Town on the 13th February 1958. Returned to the UK for training with Coastal Command on the 25th February 1963 and returned to South Africa on the 1st April 1963. Progressively modified up to Phase III standard. She was withdrawn from service on the 24th April 1978 & in storage at AFB Ysterplaat. Static display outside clubhouse at Stellenbosch airfield. Static display at the V&A Waterfront in Cape Town, cut up for scrap.

1720 / M - c/n1530, first flight on the 26th September 1957. Accepted by 35 Sqdn in January 1958. departed for Cape Town on the 8th February 1958, arrived Cape Town on the 13th February 1958. During asymmetric practice on the 18th September 1961, landed in undershoot at DF Malan airport, and was badly damaged. Repaired on site, with a hangar being constructed around the aircraft whilst repairs were carried out. Progressively modified over the years up to Phase III standard by March 1973. Tthe aircraft was withdrawn from service on the 10th March 1983, after reaching the end of its fatigue life. Initially allocated as a gate-guard at AFB Ysterplaat, she is displayed outside the WO's club, now having been sprayed in the1957 delivery colours & marked as 1717-O. Due to the airframe deteriorating & being a safety concern, she was cut up for scrap 2013.

1721 / N - c/n1531, first flight 12th December 1957, accepted by 35 Sqdn on the 30th January 1958, departed for Cape Town on the 14th February 1958, and arrived cape Town on the 26th February 1958, damaged in a wheels-up landing at AFB Ysterplaat on the 10th September 1962. Progressively modified over the years up to Phase III standard, has the distiction of being the Shackleton which using depth charges, sunk the damaged tanker Wafra in March 1971. This after attempts by the Buccaneers of 24 Sqdn to sink the ship had failed. Took part in the retirement ceremony flypast at DF Malan airport on the 23rd November 1984. Ferried to SAAF Museum Swartkops for static display in December 1984. She was used as a parts donor for the restoration of 1716.

1722 / P - c/n 1532, First flown on the 7th February 1958. Departed for South Africa on the 14th February 1958, arriving Cape Town on the 26th February 1958. On the 7th June 1960 the aircraft nosewheel assembly refused to lock down, and she landed on a foam strip at Langebaanweg. The nose undercarriage collapsed on touchdown resulting in slight damage. The aircraft was repaired and progressively brought up to Phase III (non-Viper) standard. She returned to the UK on the 28th June 1964 for Joint Anti Submarine School (JASS) course, flying from RAF Ballykelly. Returning to Cape Town on the 30th July 1964. Took part in final retirement ceremony, overflying DF Malan in formation with 1716 and 1721 on the 23rd November 1984. Retained by 35 Sqn at DF Malan in ground running condition for the SAAF Museum. Her last public flight was on the 24th September 2006, at the Africa Aerospace & Defence airshow, after which the Chief of the Air Force, felt the value of Shackleton 1722 was too high to risk by continuing to fly the aircraft, and she was grounded. This ended the famous "Pelican22"'s flying career, which had spanned an impressive 48 years! Still not 100% sure of her final flight date though?

Quote:

So the last flying Shackleton in the world was certainly 'Pelican 22', whose final flight happened on March 29, 2008. This was a typical flight which took it over the city of Cape Town, and then out over the Atlantic Ocean, then back over Robben Island to Ysterplaat AFB. This final flight was piloted by Captain Peter Dagg. The crew included flight engineer Bronkhorst and ground engineer Potgieter.

1723 / Q - c/n1533, First flown on the 10th February 1958. Departed for South Africa on the 14th February 1958, and on arrival at AFB Ysterplaat on the 26th February 1958, the aircraft suffered a hydraulic failure. The undercarriage and flaps were lowered using emergency air, but the brakes were inoperative and the aircraft ran off the runway, colliding with a brick building. The damage to No. I engine was repaired. Progressively modified up to Phase III standard. The aircraft was retired on the 22nd November 1977, having expended her fatique life. Ironically she was the last aircraft delivered, but the first to be retired. She was stored in the open at AFB Ysterplaat until sold, and in March 1987, was put on display on top of Vic de Villiers 'Vic's Viking', garage in Johannesburg. This was a three way swop, with the Shackleton replacing a Vickers Viking, ZS-DKH, which went to the SAA Museum, and the SAA museum then gave the SAAF Museum three Ventura's. 1723 was initially kept displayed in her SAAF colours, but was subsequently over the years sprayed red/white in Coca Cola colours, then blue/white in SASOL colours.

Read more about this particular aircraft 1723 and Vick's Viking Garage (click on link)

Read more about this particular aircraft 1723 and Vick's Viking Garage (click on link)

No copyright infringement intended. Happy to credit you, link or delete images. Just contact me. Not my work, just collated.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Amelia Earhart's sad demise

Dozens heard Amelia Earhart's final, chilling pleas for help, researchers say Distilled from 2 posts in the Washington Post a...

-

Pelican 16 Down: The story of a grand old lady lost in the Sahara desert Part 3 of the Shackleton MR3 in SAAF Service SAAF Shackleton 1...

-

Red 8: The only Surviving Me 262B-1 Night fighter (Nachtjaeger) Surviving samples of the world's first operational jet fighter are ...

-

Horten Ho 229 Flying Wing Role: Fighter/Bomber Manufacturer :Gothaer Waggonfabrik Designer: Horten brothers First flight: 1...